Not just a Bike Race but a Journey of Discovery

Introduction

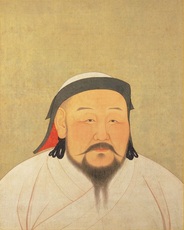

| The Mongolia Bike Challenge is an experience like no other. It is a distinctly unique and rare opportunity to race in a land frozen in the past, a land obsessed with an age over eight hundred years’ old, when Mongol Khan’s and their hordes ruled a fifth of the world with a lethal army no rival civilisation could resist. Mongolia remains trapped in an ancient time most of the western world has forgotten, as the society we are accustomed to, hurtles into a futuristic world of digital technology, dominated by laptops, iPhones, computer games, mass globilisation and atomic power. Seventy riders, from all corners of the globe, were to embark on a severely demanding journey, which would challenge physically and mentally but would ultimately forge bonds and friendships as enduring as Mongolian legend itself. |

Ulaanbaatar

| The city of Ulaanbaatar, however, does harbour some hidden charms. Around seventeen cyclists embarked on a pre-race city tour with Byra, our Mongolian guide, and we were fortunate enough to experience what little remains of traditional Mongolian culture. A visit to the Gandantegchenling Buddhist Monastery, built in its present location in 1838, and spared from destruction by communist Russia, revealed the impressive Janraisig statue towering over 26 metres high and gilded in gold. Nine hundred monks continue to practise Buddha’s teaching and we witnessed several chanting from their ancient scripture. Other highlights included the Choijin Lama Temple Museum, showcasing 1904 architecture, and the main square complete with impressive statues of the great Khan’s, Chinggis, Ogedei and Kublai, as well as a central bronze statue of Damdin Sukhbaatar astride his horse, the hero of the 1921 Revolution. The final destination was the National Museum of Mongolia, which revealed, amongst many treasures, the highly impressive weaponry and costumes of the Mongol hordes, arguably the world’s greatest and most powerful historical army. |

The Race

Landscape & Climate

Mongolian People

| The Mongolian people were extremely welcoming and friendly. During the race, the Mongolian helpers were very accommodating, while the Mongolian riders rode with spirit, on bikes most of us would have been riding ten years ago, with heavy steel frames and v-brakes. As we passed by gers, families would smile and wave and shout words of encouragement. It was particularly refreshing to see young children playing outside together and chasing horses, cows and goats. Perhaps, this life of freedom is one our own children sorely miss. After the event, race helper Billy and his Mongolian friend, Oggy, took Pete Selkrig and myself to a traditional nomadic ger where we drank the local speciality, airag, made from fermented mare’s milk, an experience that I, and my tortured stomach, will surely struggle to forget in a hurry. |

Fauna

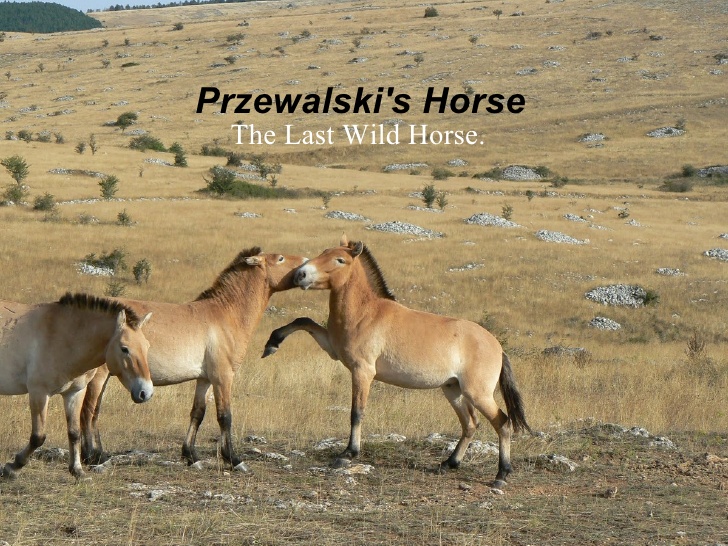

| The fauna of Mongolia is unique to this area of Asia and provided some of the most memorable moments in the race. Large herds of wild Takhi horses are numerous in Eastern Mongolia and were often sighted in the grassy plains. One unforgettable moment occurred when a herd of Takhi horses charged across the lead group of riders, a moment no rider will ever forget. This was closely followed by a similarly large herd of antelope which crossed in front of me and Brazilian rider, Breno Bizinoto. Despite working hard to keep in contact with the front group ahead, we both turned to each other with the widest of grins, exclaiming that this was what racing in Mongolia was all about. A truly magic moment. Cows blocking the road were to become a common sight, as were goats and sheep. Birds of prey would circle above, perhaps sensing weakness in some of the riders below. Marmots and mice would frolic on the dusty roads, just disappearing into their underground burrows, moments before a 29er wheel would seemingly crush their tiny, fragile bodies. Strange cricket-like insects buzzed around riders as they made their endless journey across the Mongolian steppes. |

International Family

| On a number of days, I would be isolated from the fastest group, only to find support from others in a similar predicament. It is often said that you will find your physiological equal several times during a stage race and this event was to prove no exception. On a couple of days it was my sparring partner from the Crocodile Trophy, Kristof, at other times it was Portuguese rider Jose Monteiro, or Scotsman Alan Grant (who demonstrated his toughness by riding most of the race with a shattered thumb) and on a few occasions it was Breno from Brazil. Both Breno and I are 24 hour riders and we were able to pace ourselves effectively for long sections of the race. Without doubt, I will race with these guys again in the future. That is the beauty of stage racing; it is a wonderful family that can be found all over the world and our destinies are somehow intertwined. | Other riders I met and bonded with are far too numerous to mention but I will make special mention of a few. Christof Marien, from Belgium is one of the kindest people I have ever met. He is a sprinter by trade and has an illustrious racing history. A massive 110 kg of pure power, he would frequently lead trains of appreciative riders for long periods of time, often doing 90% of the work. A number of times, I was the direct beneficiary of his generosity, as the big man dished out endless pain to groups desperate to hold his wheel. Cursed by enormous ill-luck, he was the victim of numerous punctures and stomach problems and consequently, he would drop out of the first group and into the realm of the chasers. As fate would have it, on the final day he was to remain in the front group where he surely deserved to be, benefiting the likes of Cory Wallace and other elite riders. |

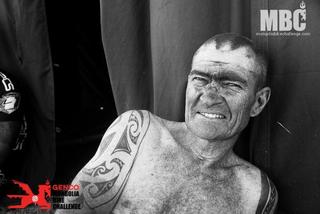

| Obviously, the elite riders are the stars of a stage race but the heroes can be found much further down the field. These guys spend far more time on the bike and have far less time to recover from a stage and prepare for the next. Of particular note, is Simon Usher, who crashed heavily on the second stage and broke two ribs. Amazingly, he rode the whole of the third stage, before being forced to withdraw with a punctured lung. At the final ceremony, he surprised everyone by turning up unexpectedly to be part of the final day celebrations, while continuing to smile and remain positive throughout. Unable to fly home, due to his condition, he ingeneously came up with the marvellous solution of taking the Trans-Siberian Railway back to England accompanied by his girlfriend! |

The Course

My Experience

Organization

Khan Warfare

| Willy Mulonia, stated that this was the most successful race yet. This was due in part to the incredibly close racing at the top end of the field. Cory Wallace, from Canada, was seeking his third Mongolian Bike Race Victory but was pushed to the very end by the enigmatic Nicholas Pettina. The following story is quite incredible, one I first heard at the back of the bus as we travelled to the Chinggis Khan Monument. The day before we left the hotel to travel to the race start, bearded Italian rider Nicholas Pettina had decided to ride 70 km to the edge of the Gobi Desert and duly set off with a friend. After travelling part of the way, the friend thought better of this expedition and turned back to Ulaanbaatar, leaving Nic to travel all alone. He eventually arrived at the edge of the desert and took a number of photographs to prove his quest had been successful before embarking on the long return journey back to the hotel. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed