Jump aboard the Three Stop Pain Train The Tour of Wessex in the biggest multi stage sportive in the United Kingdom and has been serving up competitive cycling in the quintessential English countryside since 2006. Each stage provides a unique mix of challenging, yet stunningly beautiful terrain, timeless history and ancient monuments. The event attracts riders of all levels and offers the standard 3 day route of 523 km (325 miles), a medium 3 day route of 355 km (221 miles) or the chance to participate in individual days ranging from 102 to 127 km (64 to 79 miles). Historically Wessex is one of the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, whose ruling dynasty eventually became kings of the whole country and its land approximated that of the modern counties of Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, and Somerset. The region also figures prominently in the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and where English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy set much of his work. Stage 1 - 161 km - 1,900 m Stage 1 would take us from Langport, Somerset through Wiltshire and back to the event HQ. For the first stage, I was joined by my Bigfoot training partner, Robb Cobb, and we lined up in the first group to be released from the start. The weather forecast was for rain and storms but it was still quite warm. Ten minutes before setting off, the clouds burst and it became suddenly very cold and we were left wondering whether a light race gilet was going to afford enough protection. The peloton set off at a ferocious pace as early race nerves seemed to dictate and perhaps there was a desire to ride out of the driving rain. I looked for Robb but he hadn't made the front group. I found out later, that he had been caught behind a guy who was unable to clip in and despite almost closing the gap to the lead group he didn't quite make it. I was enjoying being pulled along at almost 40 km/h but suddenly just before the start of the Cheddar Gorge climb around 35 km in, I slipped off the back having left too large a gap - I worked back on a couple of times before the elastic snapped and the peloton was gone. Left alone with no one behind, I climbed the stunningly beautiful limestone gorge in the Mendip Hills. The gorge is the site of the Cheddar show caves, where Britain's oldest complete human skeleton, Cheddar Man, estimated to be over 9,000 years old, was found in 1903. It is easy to see why this popular climb was voted one of the UK's top 10 cycling roads. It is certainly not the hardest climb, at around 4% for 4 km. Nevertheless, I was glad I didn't have to race up it and started to see some benefit to being dropped. I was eventually joined at the top of the gorge by a fast moving group of four riders and, soon after, the rain abated. By the time I reached the next big test, King Alfred's Tower, 85 km in and with short ramps of around 30%, the rain had stopped and had been replaced by warm sunshine. Despite this, wheels were still slipping at the top of the climb. But this was the final test of the day, and we motored through the descents and flatter rides towards Glastonbury. I was joined, near the end, by George Lewis, a friend I'd met on the Marmotte in 2017, and we finished the stage together. I crossed the line in 60th overall (30 km average) with Robb just seven minutes behind. Stage 2 - 191 km - 2,300 m Lining up for Stage 2 and we were again given an early drenching by heavier rain than the day before and the prospect of storms all day - several people huddled under marquees until the last moment and apparently around 15 people rode to the end of the carpark before turning round and calling it a day. This time, the start was far more sedate, perhaps those early 'race' nerves had gone and spirits had been tempered by the rain. A small group escaped off the front of our peloton, but the main group stayed together as we rode towards Swanage in Dorset and the Jurassic Coast, England's first natural UNESCO World Heritage Site. There seemed to be a large number of riders puncturing in the wet conditions and the group started to thin down to around 20 riders. We were climbing, when I suddenly noticed sealant spouting from my front tubeless tyre. I watched intently, desperate to see the hole seal as I didn't want to lose the group. Fortunately, the sealant worked its magic and very little air pressure was lost from the front tyre. I was still in the game. We passed the ruins of the 11th Century Corfe Castle, built by William the Conqueror, and one of the earliest castles in England to be built at least partly using stone rather than earth and timber. Our group was dwindling, and with 8 riders remaining, it was time to stop at the third and final feed station to take on water and other nutrition. With 80 km to go, we now worked even more effectively as a group, with constant rotation, no one sitting out for too long. We stayed together, very similar in ability both climbing and descending. The kilometres ticked passed and it seemed like no time before we crossed the finish line. I finished this stage in 15th overall and averaged 31.2 km/h and, because of the way we had ridden so well together, and the stunning coastline scenery, this was my favourite stage of the 3 days. Stage 3 - 171 km - 2,800 m The final stage had been billed as the toughest and, in this respect, it was not to disappoint. With 350 km of hard riding already in the legs and with the prospect of the toughest climbs to come, this was never going to be easy. The weather was great, however, and the sun cream was on. The pace was reasonably sedate at the start and I, perhaps foolishly, contributed too many turns at the front of the peloton. I paid the price as the hills of Exmoor took their toll. I was dropped on Quantock Hill, a 7% gradient for 2.5 km and I found myself riding solo, considerably dropping my average speed. We thankfully descended Crowcombe Hill but then Elworthy Hill, at 2 km and 10% average, took more strength from tiring legs. Sweat was pouring from every pore as I descended the viciously steep Porlock Hill with brakes fully on at times. I needed water and I as I entered the feed station, the main peloton was leaving. I was, however, content to suffer the biggest climb, Dunkery Beacon alone. After I got through the first steep section, a group of knowledgeable bystanders informed me I was only 40% up. My legs were weary as a rider passed me, who also heard that even more pain still lay ahead and he complained vehemently under his breath. We ground up several more steep sections of unrelenting 17% gradient and it was some relief to crest this monster of a climb (by far the most difficult section of road in the whole event) and start the long, more gradual descent. The route cut back on itself and I saw several riders coming the other way. I felt some sympathy that they had some brutal climbs still to come. I seemed to be alone for a long time but was then caught by a fast moving train from Norwood, south London. I jumped on this group, thankful for the company. Cothlestone Hill may only have been 1.2 km but at 10% this late into the event it hurt. Once crested we knew it was mainly downhill and flat and the boys from Norwood put the hammer down. I tried to do my bit at the front but realised I was on my limit and got to the back of a group of around 9 riders and hung on for all my worth. We finished the last 20 mile section in an average of 34.2 km/h and this helped me to finish 25th overall for stage 3. I was more than thankful for their selfless efforts. The Tour of Wessex is an amazing event, which was extremely well organised and took in some wonderful riding. It is definitely very tough and saves it's hardest day for when you are most tired - but in many respects, the scenery on this last day is the most sublime. I camped for the three nights and the Organisers provided the best portable toilets and shower facilities I have ever known for this type of event. There were even flowers in the loos - real ones! If you are looking to participate in a road stage sportive, this would be an event I would strongly recommend signing up for.

1 Comment

Tales of a Wounded, Sick and Tortured AnimalStage 1 was a challenging 50 km Time Trial The 6th edition of the Andalucia Bike Race obliterated all records: 800 riders, 33 countries represented, 30% foreigners, with World, Continental and National Champions present, several using the first UCI race of the season as a warm up to this year's Olympics in Rio.

Since then, I have returned to England and managed to cobble together some work commutes and indoor rides. But would it be enough to keep up with Stage race rival and now Bikeboard Polish teammate, Zbigniew Mossoczy? Ziggy and I have raced against each other in both the infamous Crocodile Trophy in Queensland Australia (2013), where he finished 4th and I was 5th, and in the technically difficult Sudety MTB Challenge in Poland (2014), finishing 15th and Ziggy some places ahead of me. This mountain of a man was to prove my tormentor in the southern Spanish mountains. Dawn broke, and the Bikeboard team, which also contained elite Polish pair Jakub Swiderski and Przemyslaw Maciejowski, simultaneously rose from the night's slumber. But four rushed visits to the toilet in the hotel and a final forced visit pre-race did not auger well for me. The first stage saw the riders depart Martos at 30 second intervals and the first kilometres were flat and furious. However, I was already struggling. The sight of the steep first climb blew to smithereens any lingering hope of remaining strong. The singletrack snaked steeply up the side of the mountain and despite incredible support from the enthusiastic locals, my legs and lungs spontaneously imploded. I felt pain in the glutes and the Achilles and although I was aware of the stunning views from the top of the mountain, I was in no mood to enjoy them. Zbig resorted to pushing me at every opportunity, which helped but also further destroyed my disintegrating ego. The crowd support continued to be amazing, the locals really embracing the race and the support was fervent. 'Arriba' , 'venga venga' and 'animal' they screamed as my partner continued to monster the climbs. I barely rode across the line and felt dizzy and weak. Never before, could I remember such a devastatingly hard stage. Shortly after, I was in bed and soon asleep not to wake up until several hours later. Stage 2 was destined not to happen. The Queen stage of the race was apparently the most beautiful but, like Medusa, the most brutal. A sequence of steep, serpent-like trails, climbed the surrounding Jaen mountains, ultimately rewarding riders with rapid, technical descents. But for me they would merely be a vision from my stupor and not a reality. I could not drink, never mind eat, my stomach repelling the food as if it was its mortal enemy. During the night, I felt like a spit roast, constantly turning but finding no relapse from the stabbing pain. Uncontrollable vomiting followed. As far as I was concerned, my race was over. I just wanted to be removed from the spit that cut through my core. After waking from my tortured sleep, my three Bikeboard teammates reported similar symptoms and the culprit, we believe, was chicken brought in jars from Poland. The day was spent at the local hospital, medication and injections taken and a little food consumed. The symptoms began to subside, and we looked positively to trying to ride the next day. We all dragged ourselves to the start line in Andajur, a transition stage between Jaen and Cordoba. We were now placed in gate six, at the very back of the 800 riders. Zbig and I cut through the pack, the first 20 km undulating, allowing fast speeds and the opportunity to ride with some of the stronger riders. We were treated to two difficult climbs but plenty of singletrack and some stunning vistas. We were to place 24th in Masters 40, our best position during the race. Stage 4 departed the historical centre of Cordoba from the mosque and swiftly crossed the river. Mountains, forest, animals and singletrack followed in abundance. We hit the rocky abandoned railway track and my buddy punctured, as his spoke broke free of the rim. We lost a little ground, but as we climbed La Canchuela, we were surrounded by some of the top mixed and female teams and I couldn't help but be so impressed with the bike handling skills on display. Not that skilful female bike handlers are unique, but the strength in depth here is amazing. We descended the final roman road, which was typically fast and technical and finished a respectable 28th in category. By Stage 5, my brief revival during the race dissipated. Like a dying animal, I had responded valiantly on the previous two days, but I was essentially masking weakness. The first long climb up a steep jeep trail ended in a conga line and delay going into the singletrack, which we knew would require intense concentration to avoid paying the ultimate price. Eventually, we realised that a rider had gone down hard and broken his collarbone and was being returned to the safety of the main trail. Now fatigue had hit me hard and I couldn't maintain the pace of the peloton. I dropped from one group to the next, hindered further by a malfunctioning freehub, and limped weakly to the end of the stage. Stage 6 started with a technical climb up El Reventon, just 4 km from the start. My pace was uneven and the flowy singletrack that followed, just seemed to present challenging hill after hill. The rain fell for the first time and the temperatures dropped. The final descent was made more difficult by the slippery rocks. Again I limped over the line, struggling to breathe, a pain in my sternum that would remain for a couple of days more. My race was over and I was truly cooked (unlike the chicken on the first night)! Even the professionals were struggling on the steep climbs (Lakata & Hynek) For the record, current XCM Champion, Alban Lakata (Austria) and former XCM European Champion Kritian Hynek (Czech Rep.) were the competition favourites but, on the very last day, they lost their slender 41 second lead to Periklis Ilias (Greece) and Tiago Ferreira (Portugal). This was to prove to be the closest fought edition in the event's history the winners finishing with an overall time of 18:38:24. Female World Champions Sally Bigham (Great Britain) and Katrin Leumann (Switzerland) dominated in the elite women's category finishing with a time of 23:28:38. If anyone is thinking of doing a stage race in Europe, this is definitely one of the best organised as you would expect from a UCI S1 event, with maximum ranking points for the top riders. The climbs are steep and the descents are fast and thrilling, while there is an abundance of spectacular scenery and plenty of flowing singletrack. It is not easy and a certain degree of ability is a must. My one small gripe would be that accommodation is in hotels and so the race loses the camaraderie of races such as the Crocodile Trophy, Mongolia Bike Challenge and the Sudety MTB Challenge. Consequently, organise a trip with a few mates and share the experience together - My Polish friends and I had an incredible time, one that is etched deeply in the memory, despite all our adversity. Official 2016 Andalucia Bike Race Preview

Not just a Bike Race but a Journey of DiscoveryIntroduction

UlaanbaatarUlaanbaatar, the arrival city for all participants, acts like a smokescreen, a place of deception for what Mongolia is to reveal later to her newly arrived guests. The capital city, like a hospital patient who has awoken from a twenty year coma (the Democratic Revolution was in 1990), is rushing recklessly to catch up with the rest of the world. It is a city containing over half of Mongolia’s total population, and it is racing to be at the high table of the Modern World. Coal-fired power stations, built during Russian dominance, stand juxtaposition beside gers, more appropriate to the countryside while large modern summer houses rub shoulders with poverty ridden shacks. Even in September, the veil of pollution suffocates a city built within a valley and choking her residents. Nevertheless, the city appears destined to continue its quest to catch up with the rest of the world, despite the inherent cancer of over-development.

The RaceThe Mongolian Bike Ride unfolds in the Steppe region of the countryside, covering nearly nine hundred kilometres and 14,000 metres of climbing. Landscape & ClimateThe landscape is the dominant force and the dry, grass plains stretch infinitely in all directions, interrupted only by rugged hills and mountains. Even in the heat of battle, all riders would succumb to the immense nature and mind-blowing vastness of this incredible country. Mongolia’s climate is harsh and even in September, significant temperature variations exist. Average temperatures range from -5 degrees at night to 22 degrees in the day and rain is common. The 2014 edition of the race was surely blessed in this regard. Despite two extremely cold mornings on the first two days, the weather was unseasonably hot (even peaking at 30 degrees on day four), much to the collective relief of the majority of the competitors, resulting in perfect riding conditions. Rainfall was almost non-existent, leaving competitors to concentrate on racing rather than self-preservation. Admittedly, night fall would be accompanied by a brisk, chill air and a cool wind on the final day was a reminder of how cold it could become. Mongolian People

Fauna

International FamilyThe people involved in the Mongolian Bike Race, either as a rider, event or support crew were to become part of a large close-knit family. It didn’t matter if you were Cory Wallace (Canada), Nicholas Pettina (Italy), Luis Pasamontes(Spain) fighting for overall honours, a category podium chaser or a rider whose main intention was to merely to survive the seven day ordeal, we all had two main criteria in common. We love riding mountain bikes and we enjoy the adventure of travelling to far-flung places. The camaraderie between riders is perhaps one of the greatest attractions of this type of race. Some of my greatest mountain bike friends have been discovered in these races. Indeed, the bond shared by myself and riders who also competed at the Crocodile Trophy in Queensland, Australia in October 2013 is palpable. These included Cory Wallace, who was the single biggest reason for my participation in Mongolia; Peter Selkrig, a fifty-two year old racing machine, training partner and fellow 24-hour endurance racer in Australia; Kristof Roelandts and Hans Planckaert from Belgium and Jiri Krivanek and Radim Novotny from the Czech Republic. The bond and mutual respect is simply unbreakable.

The CourseThe race itself is not particularly technical but is physically demanding and the long distances do take a toll on riders. The back-to-back 170 km days are particularly difficult, leaving little time for recovery and preparation for the next day. Racing involves riding in groups and, for many, long periods of time riding solo. But the Mongolian Bike Challenge is not just about riding a bike but about how you prepare for the following day. After crossing the finishing line the event is far from finished. A cool down is preferable but not always possible, recovery drinks need to be consumed and food eaten immediately to make use of the body’s ability to most effectively re-absorb carbohydrates. A shower needs to be taken and bike clothes quickly removed and washed ready for the following days. Then the bike needs to be cleaned and checked for any mechanical problems. A select few were lucky enough to have been able to pay for full bike maintenance and massage every day. After the presentation ceremony and a healthy and substantial dinner it would be hoped a good night’s sleep would follow, be it in touristic gers, cabins or, more usually, in eight man tents but this meant night time was invariably accompanied by a chorus of snoring and coughing. My ExperienceThe race was certainly very tough and I had my fair share of obstacles to overcome. I almost didn’t enter Mongolia, a last minute trip to collect my British passport allowing me to enter the country without a visa. The day before the first stage, I was thirty seconds into a training ride with Hans Planckaert, and while looking up at the statue of Chinggis Khan’s mother, and travelling downhill on a smooth trail, a gaping hole suddenly appeared, too late for me to react to. As my front forks fully compressed, I was launched over the handlebars landing heavily on my right shoulder, breaking the bottle cage from my saddle. I was cut and severely bruised and regular painkillers were necessary for the duration of the race. Indeed, I was unable to lift the handlebars nor was I able to drop off rock steps without stabbing pain. A more technical race would have certainly led to my withdrawal. Furthermore, the freezing starts on the first two days led to breathing difficulties and I struggled with my asthma. I resorted to ventolin in the later stages, but choking dust meant I was riddled with a hacking cough for the duration of the race. During the last two stages, saddle rash meant excrutiating pain on sitting. I also needed to adapt to carrying just a single drink bottle, with my extra bottle cages ejecting my second bottle every time I descended along rougher ground. This meant drinking a whole bottle of water at drink stations in an attempt to stay hydrated. I managed to finish 6th in my age category and 24th overall, while my three-man Croc Team eventually finished third, after leading for the first two stages. OrganizationMongolia is an incredibly difficult place to organize an event of this nature and racing incorporates a strong sense of adventure. Mongolian Bike Challenge Founder and Race Director, Willy Mulonia, has gathered together an excellent team, consisting of logistics, photographic personnel, drivers, medical staff, mechanics and masseuses. It is fair to say, that not everything ran perfectly but, considering the scope of the event and the difficulties of racing in the Mongolian landscape, the race was a phenomenal success. The mechanics, headed by the multi-talented Jordi, worked tirelessly, the medical staff stayed calm and professional despite having to deal with major problems such as broken bones, punctured lungs and heat exhaustion. Videos, photographs and race reports made it out every night on the website, although most of the competitors were unaware of this happening. Several riders did take wrong turns but would eventually find the right road, while daily postings of the results were sorely missed. The food, on the whole, was excellent, with Rosewood’s catering on two of the days particularly popular. On a couple of occasions, the food was sparse and so the recommendation, pre-race, to take a selection of snack items was thoroughly welcomed. There was little or no phone and internet access, but this is understandable, considering the extremely remote location. The start and finish locations at the Chinggis Khan monument and the 13th century Camp were excellent, as was the superb entertainment before the first day and particularly during the final celebration. The shamen fire dance, the amazing contortionist and the traditional music and singing will stay long in the memory. Khan Warfare

Nic took a different route to the one he had first travelled on but, he believed it would lead straight back to the city. Time evaporated quickly and the daylight hours began to fade. Darkness fell, and Nic was still no closer to the city. It was now dark and too dangerous to ride and so he was forced to push his bike up a hill to a nearby forest. At this point he knew he would not make it back to Ulaanbaatar and panic must have set in. It was becoming extremely cold and he had no extra clothing and certainly not the emergency blanket all riders needed to carry in the race. Fortunately, he spotted a fire burning ahead and, on investigation, he happened to come across four local Mongolians, who welcomed him and allowed him to sit by the fire. They covered him in a plastic sheet and fed him pine nuts. Despite the fire, he was still cold and with wolves howling in the surrounding forest he was unable to get any sleep. But he was still alive. The next morning he bid farewell to his life-saving hosts, who didn’t seem to understand his urgent desire to leave so he could join the other riders in Ulaanbaatar, who were now preparing to leave the hotel. Nevertheless, Nic was eventually pointed in the general direction of the city and he rode off with fresh hope. The city was soon in sight and he now knew he would soon be back at the hotel. At that moment, a Mongolian soldier stopped him at gunpoint. He had ridden straight into an army base. No matter how much Nic pleaded, the lack of communication meant that he was being treated as a suspected terrorist. The police were called out, and he was driven to Ulaanbaatar Police Station where he was able to call for assistance from the race organisers and was finally released on production of his passport. The final part of this story is perhaps even more amazing. Without sleep or food that night, he was able to not only compete in the first stage, but was to beat a strong field and win the opening day of this incredibly difficult bike race. In the end, Cory Wallace was to win overall honours but Nic was to finish a mere two and a half minutes behind. ConclusionThe Mongolian Bike Race is an event I would wholeheartedly recommend to bike riders ready to undergo a uniquely different experience as well as a physically tough race. A number of riders were not able to finish for a multitude of reasons, while the majority suffered both physically and mentally. Be ready to jump into the hurt locker on several days but also keep your eyes wide open because that once-in-a-lifetime experience is never too far away. This is a race that will live long in the memory, while the friendships made are sure to endure in the same manner as the legend of Chinggis Khan. Pre-Race – An Extremely Lucky EscapeBefore any race of this magnitude, it is critical to prepare thoroughly. Bikes have to be fully serviced and readied, equipment and appropriate clothing organised and essential spares bought. Race websites need to be scrutinised and handbooks printed off and pored through. Every race is different and Mongolia is particularly unique. For the first time in my race experience, it is a requirement to take a survival kit consisting of aluminium survival blanket, torch / light, whistle and a mirror for signalling, utilising the power of the sun. Bear Grills eat your heart out. The thing is, he probably would!

Only a couple of hours before my departure by airport bus, I was nervously waiting at The Bike Mechanic, in Balgowlah with owner, Jordon, finishing a race service on my Giant Anthem (I had chosen this bike because it is more rigid and slightly lighter than the Turner Czar and therefore more suitable for the longer distances to be ridden in Mongolia. Jordon kindly boxed the bike and I was ready to fly – or so I thought. When it comes to reading the aforementioned race handbook, I have frequently been found wanting. One year, at the 100 km Capital Punishment race, I followed a group of bike laden cars to the race start only to realise, five kilometres in, that I was actually in the wrong race and must have turned up to the 50 km, not the 100 km start line. Today, I was worried about the baggage restrictions which vary greatly between airlines. Last month, travelling to the Sudety stage race in Poland, Emirates Airlines allowed for 30 kilos and had let me fly with 35. Air China, however, only allow 23 kilos and it is impossible to buy excess baggage before flying. I was expecting to pay US $150 and with 35 kilos I braced myself for the hefty charge. Little did I know that was to be the least of my worries. I was casually chatting to a colleague from work, who just so happened to get on the same airport bus, when the bus ground to an alarming halt. I looked round to see we had turned into gridlock in the centre of Sydney at peak hour. With a nervous and embarrassed tone, the driver announced he had taken a wrong turn (damn right Columbo) and asked if we knew the quickest route back to the airport road. I had two hours before my flight departed and I visualised running through the airport gate as the plane started to taxi for take off. I gulped, anticipating disaster. We hastily directed the driver back to the airport road and, possibly quite miraculously, the traffic dissipated and we were soon moving quickly again. Disaster was averted – for now. I had booked online, and confidently strode up to the check-in desk. As I handed over my printed boarding pass and Australian passport, the assistant shook his head. Was it the weight of my bag? I hadn’t even put my bike on the scales. ‘Where are you going?’ he asked. He had my boarding pass so why was he asking? ‘Uluumbaator, Mongolia’ I replied slightly perplexed. ‘Where’s your visa?’ ‘What visa, you don’t need one…do you? ‘Can I have your ticket please.’ I quickly replied I had my British Passport. He took both passports and my ticket and disappeared. Minutes later he re-emerged and told me that an Australian Passport needs a visa. But, fortunately, I could fly out with my Australian passport and enter China and Mongolia with the British one! The fact that I had my British passport was another stroke of luck. An attempted delivery had been made to my home address just days before but, without a signature, it had been returned to DHL, the courier. I arranged, on the internet, for it to be delivered to my work address but it never materialised. Later that day, I phoned DHL and was told that passports could only be delivered to the original address for security purposes. I could either stay in all morning between 8 and 12 or I could pick it up from the airport depot. Unable to take the morning off work, the only option was to make the time-consuming journey to the airport. I nearly didn’t go. I had travelled to Poland, the Czech Republic and England on an Australian passport so why not Mongolia? But, in the end, I did go. Perhaps I have a Guardian Angel. At times, I have incredible luck. More than my fair share perhaps. For the second time in a month, my stage racing endeavours had been saved in the eleventh hour. In Poland, my saviour was a German called Andreas who I had first met at the Crocodile Trophy and who had kindly organised for a replacement brake be brought 10 hours from the German city of Freiberg. This time it was the newly attained British passport I so nearly didn’t collect. And a final point. Amongst all the drama over the visa, my bags and bike, so clearly over the weight limit, were passed through without an extra charge being levied. But I insist, please don’t try this one for yourselves… A Once in a Lifetime OpportunityIntroductionA bewildering number of Mountain Bike Stage Races exist across six continents. Some claim to be the toughest, others the most scenic, while a few boast of being the greatest. Participants often compete for several consecutive days, experiencing incredibly varied and beautiful terrain, riding across mountains and valleys, through deserts and forests and besides lakes, rivers and beaches. The pleasure of travelling to new countries and becoming acquainted with new cultures is guaranteed to please no matter which event is chosen. Nevertheless, one race which appears to stand alone, in so many extraordinary ways, is the Mongolian Bike Challenge and it ought to be at the top of any competitive mountain biker’s bucket list. Landscape

Climate

Fortunately, the Mongolian Bike Challenge takes place in September, when average temperatures range from -5 degrees at night to 22 degrees during the day with 12 hours of daylight and a high possibility of light rain, although thunderstorms, moderate rain and even moderate snowfalls (usually in late September) may be experienced. People and LifestyleUndoubtedly, the most striking factor is sure to be the contrast between Ulaanbaatar, the arrival point for visiting bike riders, and the countryside, where the race will take place. Ulaanbaatar is an enormous city of traffic gridlock, thriving business and sinful nightlife and is one of the drabbest cities on the planet. And yet it is the capital city of one of the most beautiful and hospitable countries on earth. Beyond the chaos of the capital, the remoteness of the people has meant Mongolians follow simple nomadic lifestyles, where living conditions are rustic and unsophisticated. The home is still the Ger (or Yurt), a fur-lined tent which can be disassembled in less than an hour and transported by two camels (or more often a truck nowadays). The internal layout is always the same, with the door facing south to avoid the northerly winds and to catch the most sunlight. Men should enter to the left (west) to be protected by the great sky god, Tengger, women to the right (east) under the protection of the sun. Guests should move towards the back, and a little to the west which represents the place of honour. The back of the ger (the khoimor) is also where the elders and the most treasured possessions can be found while in the centre there is a small table and chairs. Family members are forced to interact, share everything and work together resulting in tighter relationships between relatives. Nomads are likely to move 2-4 times a year but where grass is thin this may increase.

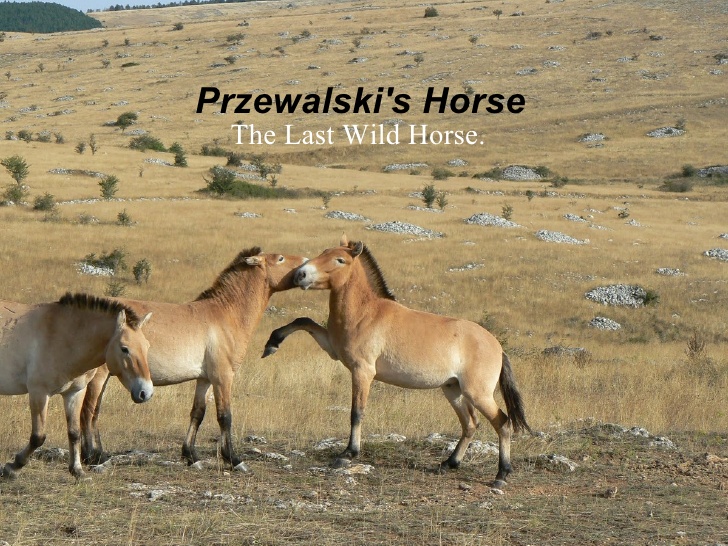

Mongolian FaunaMongolia is a naturalist’s dream and is the last bastion of unspoiled land in Asia. Numerous species, only found in Mongolia and Central Asia, are able to survive and flourish in spite of the harsh climate, widespread hunting, which is still a major part of nomadic life, limited protection from a penniless government and the communist persecution of Buddhists who had attempted to set aside areas as animal sanctuaries. Indeed, each year the government sells licenses to hunt 300 ibex and 40 argali sheep (both endangered species), in order to raise over US$500,000. Overgrazing from sheep and goats further exacerbates the problem. Mammals of the Steppe

Birds of the Steppe

Other Unique Mongolian Animals

Conclusion The Mongolian Bike Challenge is a race like no other. Located in a country where time appears to have stood still, in a land which remains as pristine as it was a thousand years ago and inhabited by unique animals found nowhere else in the world. The people continue to live like our distant ancestors lived, in simple dwellings without most of the trappings of our modern everyday lives. A country where nature is king, in the form of the vast plains and majestic mountains and the climate is constantly changing and imposing its will on her people. Those who choose to take up the Mongolian Bike Challenge are sure to leave with an imprint of a distant and remote world forever etched upon their psyche. The Enchantment of Australia's Toughest Stage RaceSeveral events claim to be the longest and most difficult mountain bike stage race in the world and the Crocodile Trophy is no exception. Offering a diverse mix of riding, the Crocodile Trophy involves nine days of racing, incorporating singletrack, rough and rocky mining trails, undulating hills more akin to road racing, a 163 kilometre Queen stage and a 38 kilometre Time Trial. The race begins in Cairns and winds its way through the lush rainforest of the Atherton Tablelands, into the dry and dusty outback. The roads are rocky and steep, or long and corrugated, but essentially always rough. Spectacular lakes and wildlife morph into quaint old mining towns and working cattle stations. In the later stages, riders enter small indigenous townships surrounded by sandstone escarpments, before returning to the tropical native bushland, crocodile inhabited rivers, pristine coastal plains and tall mountains, and finishing in Cooktown which overlooks the majestic Great Barrier Reef. In October, the climate in North East Queensland can be unbearably hot and humid, adding further challenge to a profoundly arduous race.

The Il Pastaio / Rocky Trail Racing team arrived several days early, in order to acclimitise to the hotter conditions. Team Captain, Martin Wisata (M1: 30-39), was preparing for his fourth Crocodile Trophy adventure and would have the advantage of knowing the parcours. Peter Selkrig, an ex-pro road rider with a wealth of riding experience in a multitude of disciplines and silver medalist for his age group at the WEMBO Solo 24 hour, would not only be one of the main contenders for the M3 age category (50+) but would undoubtedly mix it up with the elite riders. I was merely hoping to ride competitively in the M2 (40-49) category. Having won entry into the Crocodile Trophy by beating the Masters field at the Rocky Trail 12 hour in August, I was fortunate to be riding in a stage race which is part of many riders' bucket list. This would be my first stage race, and with just four years of racing behind me I was about to find out I still had so much to learn. Stage 1: My first impressions of the other riders had been one of awe. There were many Europeans, several with strong road backgrounds, and I feared the worst, believing I was out of my depth. However, the first stage would suit my mountain bike skills, involving five laps of a six kilometre circuit of Smithfield's iconic trails, located just a short ride from the centre of Cairns. Smithfield will be the venue for the UCI World Cup and World Championships in 2014, 2016 and 2017 and so it came as no surprise to find the trails are a pleasure to ride, with only a few short pinch climbs, and fast flowing descents. During the final two laps and with temperatures nudging 33 degrees, a number of European riders appeared to wilt in the heat. Furthermore, the stage took a toll on riders who may have lacked the skills necessary for singletrack riding and amongst those who crashed was one of the favourites for the M2 category, Austrian Wolfgang Mader, who broke his finger and was unable to complete the first lap. Reflecting the spirit embodied within the Crocodile Trophy, he would continue to endure pain and discomfort but would eventually make it to the finish line at Cooktown. Stage 2: Travelling from Cairns to Lake Tinaroo, this breathtaking stage took riders through stunning rainforest into the Atherton Tablelands. One hundred kilometres of racing and 2500 metres of climbing, steep uphills and exhilarating descents would provide an altogether different test to the first day and those riders with a road background would be far more at home on these trails. After a neutralised start, involving a police escort from the centre to the outskirts of Cairns, we arrived at the lower realms of the first big climb. As is normal in these races, the start was explosive and my heart rate was soon near its maximum. The asphalt turned to gravel and the steepness of the climbs brought many of the riders around me to their knees, forced to push their bikes up the forbidding hills. After what seemed like an eternity, the mountain withdrew its fury and levelled out. My right thigh had already started to cramp and the rest of the ride needed to be approached in a manner that would allow me to nurse my already aching body to the finish over sixty kilometres away. I was alone as I turned onto the road which cicumnavigates beautiful Lake Tinaroo. I passed a junction but was not really paying attention. Surely this was not an official turn-off. I rode five kilometres but there were no race signs. I did see a small pink ribbon on the other side of the road but perhaps it was from a previous race. Twelve kilometres past and I now thought I would surely have to turn around and climb back to the original turn-off. I decided to continue on and, when I eventually spotted a Crocodile Trophy sign, I felt strangely invigorated and powered through the final ten kilometres to the finish. Stage 3: With nearly 3000 metres of climbing, this was expected to be another difficult stage. By the time we had crested the first long fireroad climb, used extensively during the National Marathon Championship in April, the main group had splintered, but we were about to be rewarded as we entered the new Atherton Forest Mountain bike trails and the purpose-built downhill. I would have thoroughly enjoyed this, but with temperatures certain to rise, I felt compelled to stop three times to recover my second water bottle which kept ejecting itself from its cage. A number of riders came to grief in the fast, winding singletrack section that followed and then we made our second visit to the fireroad climb. At the top, I found myself with Belgium riders, Kristof Roelandts, and Liesbeth Hessens. During the final 35 kilometres, my Belgium counterparts and I shared the pace-making. I was amazed at the strength of Liesbeth, the eventual winner of the female category, and she was able to drive the group for extended periods of time. I knew M2 rival, Kristof was breathing down my neck and so I tried to break away several times but was eventually reeled back in. Not being able to break this partnership, I decided to wait to the finish, where I was narrowly beaten in a closely contested sprint. This was certainly a stage that suited a mountain biker and so it was no surprise that Cory Wallace was able to utilise his superior mountainbike skills and take first place in the elite category. Conversely, Sander Cordeel, a Belgium pro rider from Lotto Belisol crashed and was airlifted from the course by helicopter. In M2, I moved into third place overall, although a mere 13 minutes separated third through to sixth. Stage 4: I went into today’s stage feeling confident. My body was holding up pretty well to the gruelling ordeal of my first ever stage race. However, the nature of the racing was about to change dramatically into the unfamiliar territory of road riding. My lack of experience riding in pelotons was to cost me dearly. I failed to spot race leaders, Cory Wallace and Mark Frendo, move to the front and, as the pace lifted, I started to drop back. Suddenly, we hit a rough, steep hill and all my main rivals came flying through, leaving me desperately clawing at shadows. I was off the back and in no man’s land. I attempted to re-join the small group ahead but I realised that even this would not be possible and relented in my chase. Due to the rough rocky trails, several riders were even less fortunate. Most noticeably, elite Welsh rider, Matt Page, punctured three times, was obliged to wait for a slower rider to supply him with a third tube and ultimately lost thirty minutes on the race leaders. On leaving Depot 3, I was able to jump onto the back of trusty team mate Martin Wisata and when he put the hammer down it was as much as I could do to just follow his tracks. The final thirty kilometres passed rapidly as I was towed to the finishing line at Mt. Mulligan. This was a great show of team work and I was the beneficiary of an abundance of selfless work by Martin. Stage 5: The Queen Stage of the race involved riding the 163 kilometres from Mt. Mulligan to Granite Creek Dam, incorporating 3000 metres of climbing and described in the road book as ‘rough and unbelievably hilly’. The initial 45 kilometres of this stage were, once again, played out in a fast-moving peloton. I was starting to learn the intricacies of this type of racing, reaping the benefits of Pete Selkrig’s extensive knowledge from his previous experience as a professional road rider. I was feeling reasonably comfortable until we approached the first of the five feeding stations. Pete warned me of what was about to happen but I was still caught out. With the group being fairly large, riders were keen to get to the water and energy taps, fill their bottles, and leave quickly in order to remain in the main group. On sighting the Depot, I was suddenly swamped by nervous riders and then unable to get to the hydration taps. I left with two other riders, as well as race leaders, Cory Wallace and Mark Frendo. While we were able to bridge the gap I was soon to pay dearly for the energy expended. Only a couple more surges and I was expelled from the back of the group, and left to ride alone for the next 22 kilometres. As we approached Depot 3, a gate lay ahead, slightly ajar. At the last moment, I thought I saw a gap to one side and sped towards it. The Marshall screamed out that it was a barbed wire fence which I just couldn’t see because of the glare of the sun. I braked hard and, although my bike stopped, I was catapulted onto the top of the fence. Blood oozed out of my left arm and leg but, in the heat, the blood combined with sweat and dust to congeal quickly, allowing me to finish the stage strongly, moving me up to 18th overall, my highest position in the race. Stage 6: After approximately fifteen kilometres, the rolling hills were briefly replaced by a longer steeper climb and the group fractured completely. Once again, the peloton was gone and I was isolated for a long period of time. Between Depot 2 and 3, several riders began to struggle due to a lack of water. This whole section was the most challenging of the stage and included several steep climbs along the technical, but stunning, old gold mining trail. The sun was now high in the sky and with temperatures touching forty degrees I was starting to suffer in the heat. Even whilst travelling downhill, the deep sand made progress slow and cumbersome. On finally reaching Depot 3, quite a few riders had gathered there, some fully submerged in a nearby creek! The last 35 kilometres were mainly on wide, sandy roads where I was able to hook onto two Belgium M1 riders and we began to swap turns as the road opened up. One of the riders was struggling with severe saddle sores and so two of us took the major pace-making duties. As we approached the finish, a bee flew into my open shirt and I was stung several times, causing me severe pain until the intruder was released. Stage 7: Fortunately, the Course Organisers had amended their original plan to make this stage the world's longest ever individual time trial reducing the distance from a massive 96 to just 38 kilometres. Once again, I received excellent information from Pete Selkrig on how to most successfully ride a time trial but when I tried to apply the advice I had pre-race, I hit the road corrugations and began to struggle to keep my rhythm, to finish a disappointing 36th overall. Stage 8: This 113 kilometre stage involved travelling almost the first seventy on flat, wide corrugated dirt roads and so it would be important to stay in the peloton for as long as possible. After Pete, Martin and I had spent a few minutes off the front of the main group we were reeled back in. The usual chaos ensued at the first feed station and, shortly after, I was dropped once again and chasing shadows. To make matters worse, I now had a head wind to contend with for the next thirty kilometres. I ground away, alone, until I reached Depot 2 where I was able to work with other riders, providing a degree of respite from the wind until the end of the stage. Final Stage: The last leg of the Crocodile Trophy was only 50 kilometres, flat and sandy until the finish, culminating with an iconic kilometre climb of up to 30% gradient to the top of Grassy Hill. An early crash in the peloton was an omen for a day of carnage. Twelve kilometres into the race, I punctured and the whole peloton, once again, waved me goodbye. After twenty kilometres, running with his bike, Polish cyclist Zbigniew Mossoczy, came into view. His free hub had seized up. I thought he would have an extremely long day ahead but, bearing testimony to the camaraderie between the riders, he was advised to secure the cassette to the spokes of the rear wheel with cable ties, allowing him to ride the final part of the stage. Ingenious! Whilst crossing several creeks with warning signs about crocodiles, this was one place I knew I didn't want to stop with a mechanical. As I reeled in other riders, I became more aware of events that had preceded. M2 rival, Kristof, was holding his left arm awkwardly and had blood-soaked bandages on his elbow. He had crashed in the peloton earlier, hitting a hole which he couldn’t see for the clouds of red dust being thrown up from the riders ahead, and I later found out that he had needed stitches within his torn arm muscles. As I started the steep hundred metre climb to the top of Grassy hill, I passed another rider from the Amy Gillett team, who had crashed and broken his wrist. The climb proved tough and it was a relief to get to the steps that led to the finish. The Crocodile Trophy was over and I was extremely satisfied to finish fifth in M2 and 22nd overall. Peter won seven of the nine stages to win the M3 category and Martin finished higher than ever before, allowing the Il Pastaio / Rocky Trail Team to finish second in the Team Classification. On final reflection, this has been a great experience and, being my first ever stage race, I have learnt some valuable lessons particularly about riding in pelotons. The event is superbly run, the course being carefully planned out, admirably supported by a large support crew, including medical personnel, chefs and cooks, media, quad drivers, marshalls and massage therapists. The camaraderie between the riders, from over fifteen different countries, with a diverse range of experience and ability makes this event a truly remarkable one which will remain long in the memory. Next year, the rumour is the race will be sanctioned by the UCI, with most of the stages being more technical and better suited to mountain bikers. This certainly sounds like a winning formula and can only enhance the status of this already iconic race. The sixth and final day was upon us and, despite tiring limbs and general fatigue, I was quite looking forward to this stage. Most riders were expecting a difficult day, with three major climbs looming and with the prediction of tough and technical singletrack across the border in the Czech Republic, but I remained optimistic that I could finish the race with a good performance and maintain my place of fifteenth in the General Classification for M2. Having conceded some time to most of my closest rivals in the last stage and with the next two riders under two minutes behind, I would need to live up to my own pre-race expectations. As we were now accustomed to in this race, the first climb was long, but, for once, not technical, and was followed by a fast descent allowing enough time to recover for the next, slightly longer hill. Part of this descent involved a steep drop down a long mud slide – not for the faint-hearted but incredibly satisfying when the bike slid, rather than rolled, to safety into the distant abyss. As is the norm in these races, I soon recognised some of the riders around me, those who are my physiological equal. Indeed, it is possible to judge how well you are going on any given day by ascertaining which of these riders are ahead or behind you. I caught Mike Blewitt and Imogen Smith at the Mechanical Aid Point and we rode together for a few kilometres. Rain started to fall, and bearing in mind my poor performance the previous day when I became wet and cold, I toyed with the idea of pulling on a light rain jacket. Mike and Imogen had already decided to do this but as I prepared to pull the jacket out, the rain stopped and the sun appeared briefly, but enough to convince me to discard the idea. When American Elite female, Megan Chinburg , moved past Imogen, I followed her wheel up the next short climb whereas Mike and Imogen failed to respond. We worked together for a while but on the next long descent I left Megan behind to seek out other riders further up the course. We were now riding across the border in the Czech Republic, but the dreaded mud and accompanying angst failed to materialise. The singletrack was incredibly enjoyable and flowed rather than frustrated. There was one section, however, which involved wading through knee deep mud and slime but this was for only a relatively short time and the trails returned to their benign ways. Eventually, we crossed back into Poland, and for the first time in this race, we were riding on sealed roads. I had caught Peter Selkrig and Garry James at the bottom of the descent and I cheekily rode in their slipstream. Assured of second place in their category, they were riding in a relaxed manner and appeared to be enjoying their day out. We were now on the final climb of the event and this proved slightly more technical than the previous ascents. A lot of walkers were in this area and they appeared bemused as to why so many bikers were struggling with body and machine up these steep and rocky mountains. The course spat me out onto a main road and I found myself in a convoy of cars, jumping Tour de France style, from behind one to the next. I was cautious not to miss the turn off back into the single track, having gone off course just two days earlier. The final descent proved less technical than I had imagined, and I finished the race as strongly as possible. I crossed the finish line, extremely satisfied with my performance, which was a vast improvement on the day before. I finished in a time of 4.46.50, 15th in M2 and 62nd overall. I maintained my overall position of 15th in the M2 category and finished the whole race in a time of 22 hours 44 minutes. The Sudety MTB Challenge is a fantastic race, which incorporates numerous technical trails in stunningly beautiful surroundings. I would wholeheartedly recommend this race to experienced riders, looking for a true mountain bike experience. No doubt it is a tough race and it lives up to its motto of ‘no bullshit, no compromise’. The climbing can seem endless, be it on and sometimes off the bike, the steep technical descents must be ridden with one hundred percent commitment and the fast descents without fear. Thirty-four countries and five continents are represented, with a strong Euro presence and a high calibre of rider, but the atmosphere is exceptionally friendly and Race Organiser, Grzegorz Golonko,has managed to develop an event incorporating well managed accommodation, ample refreshment, well organised mechanical and medical support, friendly drivers and a great team of masseuses and highly professional photographers. Personally, I can’t think of a good reason for not returning to the Sudety MTB Challenge in 2015. Post Race Comments:Andreas Ueberrhein (Germany M1) - Next year, I'm going to return to the Sudety and I'm going to lose 10kg (So we will check to see he has dropped from 96 kg to 86 kg in one year's time).

Phil Welch (Australia M2) - A brilliant introduction to stage racing in Europe. I will definitely be back next year! I awoke to the sound of rain and this continued for the duration of Stage 4. Although this was the shortest stage, at only 46 km, it was to prove the hardest 46 km I’ve probably ever ridden. The general profile showed the route would rise to over 1000 km above sea level and would involve almost constant climbing.

The first hill rose to 600 metres and was not technical and, as a result, was ridden relatively quickly. We then turned into the singletrack and almost immediately dived down a steep mud chute, meaning braking involved sliding all the way. The problem was it just continued to go down and so it was a great relief to feel it level out and for bike and rider to remain in one piece. Shortly after, I was caught by Mike Blewitt and Imogen Smith, the Australian mixed pair, and we were able to swap turns along a rare, flatter section. I was amazed at how effectively they worked together almost symbiotically and with a thorough understanding of the other person’s needs. Soon after I hit the front, they dropped back and I didn’t see them until much later in the stage. The trail continued to rise and the rain fell harder. At the half way checkpoint, I was progressing reasonably well, but perhaps the ever increasing leg fatigue or the four previous days of extreme exertion were about to catch up with me. It may have even been due to the fact I hadn’t slept too well the previous night, or it may have been the cold, wet conditions causing me difficulty. Indeed, I perform much better in extreme heat than in cooler conditions. Whatever it was, I began to struggle up the endless rocky and muddy climbs. Normally, I am progressing through the field late in a race but today I was slipping back. I continued to struggle and became colder and colder. I hoped the endless climbing would warm me up but it didn’t. I had a spray jacket but I decided, perhaps incorrectly, not to put it on. I pushed my bike up a long, steep hill and kept slipping on the wet rocks and roots. It was tough going for me but some of the Europeans were far more adept at walking up these steep ascents and caught and passed me. I tried to follow their footsteps but without success. Perhaps I need to train in this particular aspect of our sport! We later hit a shallow, rock-strewn river and climbed up it for a few kilometres. It proved fairly technical and required a great deal of concentration. I continued to slip back through the field. It was here that Mike and Imogen caught me and so I tried to squeeze any remaining strength from my tiring body. After riding together for a number of kilometres, Mike hit a pedal on a rock and I was able to approach the final insanely steep descent alone. My hands were sore but I managed to control my bike through the large, rain-soaked rocks that littered the single track descent and reached the bottom, which also happened to be the finish line. Andreas from Germany followed me over the line, disappointed he had missed beating me by just one position. I was exhausted and cold and quickly washed my bike and showered (unfortunately in slow running, cold water). Soon after dressing the blood began to return to my extremities and I was able to reflect on a disappointing day in terms of my performance. I finished in a time of 3.35.16, with an average speed, albeit a slow stage, of just 12.3 km/h. I was 19th in M2 and 71st overall and I remain 15th in M2 in the General Classification. Tomorrow is a massive day. I, therefore, started my recovery as early as possible by immediately eating and drinking and treating myself to another leg massage. The fifth and final stage will cover over 79 km and three challenging climbs and a network of extremely technical trails await. Stage racing is all about recovery. It is essential to eat immediately after the race, in order to make the most out of the body’s ability to effectively absorb carbohydrates post-exercise. Rehydration is critical, as is replacing electrolytes such as sodium and magnesium. Taking care of the muscles by reducing soreness, flushing the lymph system and assisting blood circulation to remove waste products is also important and massage is one method of achieving this goal. With a reasonably early finish yesterday, I decided to receive a massage from the masseuses at the Sudety Event Centre. I had two people (a guy and a girl) work on my legs and I can truly testify that they take no prisoners. I regularly receive massage but this was not what I was used to. I jumped, flinched and squirmed as the girl asked me to relax again and again. Relax! Impossible! And I thought the race was ‘brutal’. The girl told me she preferred the word ‘professional’ but I still thought ‘brutal’ was far more apt. Regardless of my discomfort, the results were impressive and my legs felt considerably looser, leaving me confident in the knowledge I had done as much as I could to prepare for the next day’s stage.

We were greeted with warm temperatures, ideal for racing. The first few stages had centred around the small town of Stronie Slaskie, but today we were due to leave our Polish base camp and travel through the Sudety mountains to the village of Bardo, sixty-nine km away and incorporating over 2100 metres of climbing. The start of the race meant travelling through the streets of the town and the Peloton ebbed and flowed as it made its journey past traffic islands and roundabouts. Soon we hit the first hill and 600 metres of solid climbing lay ahead to warm the legs up and clear the lungs. We hit the highest point of the race after ten kilometres and the road book showed the next sixty would be generally down. What it didn’t show was the amount of technical singletrack and the steep, rocky descents which lay ahead. A high degree of concentration was required to negotiate the heavily rooted and rocky singletrack. One rider had pushed his way to the front of our small group, provoking no small amount of angst from some other riders. As he struggled to ride smoothly, riders would squeeze past him until I eventually arrived behind him, he hit a large root and was catapulted over the handlebars. I never saw him again. We wound our way through stunningly, lush forest and I began to worry about losing my way. That’s not to say the course is not well marked out – there are frequent signs, tape and painted arrows on the ground clearly showing the route. Having someone ahead helps a rider to concentrate on flowing through the corners and riding smoothly. It was therefore a blessing to catch Peter Selkrig and Garry James and spend a few moments following their lines. Ironically, four of us travelled a kilometre down a trail into a small clearing but we realised there were no arrows. Up the hill we rode before cutting through the trees to rejoin the race. At times, we would emerge from the lush forest, the clearing offering up stunning views of the Sudety Mountains, a reminder of how beautiful the location is where we are riding. At other times, we plunged back into the forest and descended insanely steep single trails. These descents could continue for up to 300 metres and my fingers and hands were left burning from the constant pressure applied to the brakes. Needless to say, it is imperative to concentrate fully at these times and the day certainly claimed a few victims. I passed a French rider, who was holding his arm limply and when I asked him if he was alright he shrugged. At the final checkpoint, I informed the officials and was impressed to see how quickly they reacted in order to prepare medical care. Most of the second half of this stage was ridden alone and so there was to be no sheltering behind other riders, leaving me to expend a lot more energy than is ideal to reach the finish. This stage definitely shook up the overall standings with big time gaps appearing between riders that were previously only a few minutes apart. Perhaps the Sudety MTB Challenge is starting to bite considerable lumps out of its participant’s spirit. I finished the day 13th (M2) and 58th overall in a time of 4.52.45. I remain in 15th place in the M2 General Classification but with Zbig now 6 minutes ahead after riding strongly all day while many of the other M2 riders losing large amounts of time. Tomorrow’s stage is shorter, at 44 km but extremely technical and essentially involving climbing all day! Once again, the build up to this stage was far from ideal. After replacing the rear tyre and being supplied with Stan’s goo from event winner from five years ago, Pawel Wiendlocha from Poland, the tubeless valve continued to leak. Eventually, I took the valve cap from my spare wheel and the tyre appeared to seal. The following morning, as I was adjusting the pressure in the front tyre, the valve broke in half. To solve this problem, I utilised the spare wheel again, by salvaging the core from the valve. I arrived at the starting gate, uncertain I would survive the day intact. I took a second tube as an extra precaution.

A slightly longer stage of 67.5 km with just over 2100 metres of climbing lay ahead. If I could survive the day without any mechanicals, I was certain I could register a decent performance. The early climbs were not technical but still split the large field early. My Polish rival, Zbig, was up ahead and I made it my aim to beat him and endeavoured to close the 8 minute lead he had over me from the first two stages. The temperature was in the low 20’s, with a threat of a later thunderstorm. However, conditions were to remain perfect throughout the day. I have now become accustomed to the nature of racing here. Work hard to crest the mountains, then recover on the warp speed descents before doing it all again. Climb…Descend…Repeat. This might sound like I’m doing the race a disservice but it is actually a great way to race and the varying terrain provides plenty of variety, not to mention some stunning views from the highest peaks. Unlike yesterday, where I had punctured early, today allowed me to work with riders of similar ability, and we were able to share the work on the climbs and flatter sections (not that this race has too many flat sections – it’s either up or down. My group swallowed up Zbig and on the longest climb of the day he dropped back. He informed me afterwards that he always had me in his sights but a puncture put paid to his attempts to stay with me. One feature of this race is the mud and slippery thick tree roots and half way through this stage I found myself struggling with this technical form of riding. I was not alone however, and as the trail began to rise, even the most gifted riders were reduced to walking. On the last climb, a group of about six riders reformed containing the impressive Swiss female elite rider, Andrea Kuster. As we descended some steep singletrack the pace increased on one section and I felt my bike slip from under me. I someone regained control and heard Andrea squeel from behind. She had done the exact same thing but we had both managed to stay upright and had probably avoided a serious crash. We crested the top of the climb together and began yet another insanely fast descent. I have to express my amazement at the skills of some of these female riders as I saw her disappear into the distance, chasing podium glory. I finished in a time of 3.59.50 (14th in category and 64th overall), beating my Polish rival, Zbig by ten and a half minutes and moving to 15th (Masters) in the General Classification after the first three stages. I cannot speak more highly about this race. It is well organized, and the race trails offer incredible variety and challenge. I am looking forward to the final three stages and I hope to continue to ride strongly. |

Author

Categories

All

Stage Races

24 Hours 7 hour Enduro Series 12 hour Enduros 6+6 hour Enduros Archives

August 2021

|

| CycoActive - Professional Endurance Cycle Coaching |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed