|

Valencia lies on Spain's southeastern coast, where the Turia River meets the Mediterranean Sea. Spain's third largest city was founded as a Roman colony in 138 BC with the Latin name Valentia, meaning 'valour', and later, during Muslim rule, as Medina at-Tarab or the 'City of Joy'. Valencia has an agreeable subtropical Mediterranean climate and one of the mildest winters in Europe, with episodes of heavy rainfall in autumn. Valencia is an excellent city to explore, with many fascinating historical landmarks. The Cathedral of Valencia overlooks the Plaza de la Virgen and the Plaza de la Reina and reputedly houses the Holy Grail, the holy chalice used by Jesus during the last supper. Every Thursday, at its gate, the Tribunal de las Aguas (Water Tribunal) is held, declared Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2009. The Barrio del Carmen is the ancient district which grew between the Islamic and the Christian city walls, with narrow, cobbled streets that will transport you back in time. The old Silk exchange or Lonja de la Seda, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is a gem of gothic architecture and was a main trading point on the old silk route. Along the coast, you will find the Royal Marina and Malvarrosa Beach, with unique buildings and where many important cultural events take place. The Albufera Natural Park lies to the south, with a huge lake, rice fields and unspoilt dune beaches and where paella was born. Due to continual flooding, the course of the river Turia was altered, giving rise to a 9km garden that runs through the city that is home to several sports facilites, children's playgrounds and 18 bridges. The most futuristic architecture you could hope to find is also found here in the form of the City of Arts and Science. Valencia's own Santiago Calatrava was responsible for much of the architecture that includes a colossal eye or Hemisferic, which houses an IMAX cinema, Europes largest aquarium, the Oceanografic, an interactive Science Museum, and the impressive l'Assut de l'Or bridge. Valencia boasts 156 km of cycle paths and 40 ciclocalles, which are streets that prioritise the bike, with 30 km speed limits. During my visit, I was able to explore the Parc Natural de la Serra de la Calderona, which is around 20 km north west of the city centre. The riding here has featured in several editions of La Vuelta and is extremely beautiful, with a mixture of long and steady and short and steep climbs. For example, I rode the Puerto L'Oronet, an 8.6 km climb rising to 493m and Alto Segart, a category 1 climb of 9.2 km, with gradients up to 22%, so make sure, unlike me, you have the correct gearing on your bike! For anyone who is interested in riding in Valencia, then I would suggest riding the Marcha Ciudad Valencia International Gran Fondo, competing in one of three distances, 190 km, 105 km or 76 km, and due to take place 17-18 September 2021. The lead organiser is Javier Castellar, a Spanish professional cyclist in the 80's, whose arguably greatest success was beating the legendary Bernard Hinault at Camp de Morvedre in 1985 following two climbs of the Alto Segart. He is now committed to fostering a passion for cycling through the organization of exciting cycling events, and during my visit he organised the publicity for the upcoming Gran Fondo, along with a filmed promotional ride with 2008 Olympic Gold medallist, and recently retired Spanish professional cyclist, Samuel Sanchez.

1 Comment

2. Faro de Formentor (Formentor Lighthouse)SummaryAround 35 km in length, over 800 m of climbing, breath-taking views, remarkable engineering and a near perfect road surface makes this ride arguably one of the most enchanting in the world and certainly a ride not-to-missed when visiting Mallorca. HistoryItalian engineer, Antonio Parietti built the road to the Lighthouse eight years before the road to Sa Colobra in 1925. Previously, the active lighthouse, which was built in 1863, was only accessible by sea (climbing 272 steps cut into the steep cliffs) or by negotiating a meandering 17 km mule track. The remote and precarious location made this a remarkable feat of engineering. Formentor is the highest lighthouse in the Balearic Islands, built 210 m up on the high and precipitous cliffs. The area has served to be an inspiration for many artists and inspired Pollenca's most famous poet, Miguel Costa i Llobera (1854-1922), who wrote 'The Pine Tree of Formentor'. Agatha Christie visited Port Pollenca in the early 20th century and wrote of 'a view that in the misty haze of a fine morning had the exquisite vagueness of a Japanese print'. Indeed, the Hotel Formentor, was opened in 1929 by German-born Argentinian millionaire Adam Diehl, who had a dream of creating a space where artists could draw inspiration from their surroundings. Visitors to the hotel include the Dalai Lama, Winston Churchill, Charlie Chaplin, John Wayne, Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly. Today the area is one of the most photographed and portrayed places on the island. Cycle FactsThe Formentor road consists of two category 3 climbs with shorter, punchier ascents for good measure in between, making this a ride that is achievable by the majority of cyclists. Climb Breakdown0-3.5 km: Leaving Port Pollenca, prepare to negotiate 223 m of climbing at an average gradient of 6%, while drinking in views of the attractive fishing port below and arriving at the El Mirador de Sa Creuta, a popular lookout for tourists and locals.

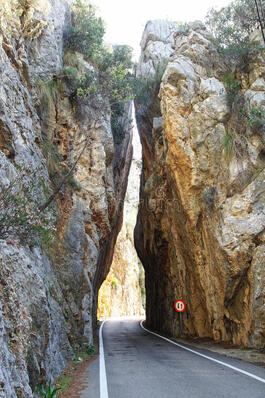

KOM: Alberto Contador - 6.48 (Apr 25 2019) 441 average watts; 29.3 km/h average speed QOM: Elisa Longo Borghini - 8.36 (Jan 14 2020) 23.1 average speed 3.5-16 km: Descend down towards Formentor Beach and into a Pine Forest, where you climb gradually towards more rugged and barren terrain, and a sharp climb revealing the crystal clear turquoise waters of Cala Figuera Beach, before ascending into a 300 metre tunnel. After climbing up and out of the tunnel the road levels out to reveal the snaking curves that will draw the rider towards the headland. The views here are stunning and the riding is sublime but perhaps not for the faint of heart. The road undulates and suddenly reveals a stunning vista of the lighthouse before plunging down and then back up to the lighthouse itself, where you are most likely to be greeted by the local goats that line the surrounding cliffs. On a clear day, it is possible to see the neighbouring island of Menorca from here.. Return to Port Pollenca: After the initial descent, brace yourself for a steep 1 km climb with gradients of around 15% taking you up 90 metres followed by a less aggressive climb and then an exhilarating descent back through the tunnel and the pine trees and finally up the cat 3 Mirador Formentor (3.45 km; 252 m; 5%) before the final descent back into Port Pollenca. Optional Extension: Talaia d'Albercutx (Pepperpot): A rougher, sometimes pot-holed road of around 2.5 km (between 6-9% and 150 metres) leads to the Pepperpot, rewarding the brave with stunning views over Pollensa Bay and the Tramuntana Mountains. 1. Sa Calobra (The Cycling Serpent)SummaryThe best known and toughest climb in Mallorca, Team INEOS's unofficial pre-season testing ground and a magnet to tourists of all kinds. A twisting ribbon of road in the Serra de Tramuntana Mountains, which snakes down limestone cliffs from the peak of the Coll del Reis (Neck of Kings), to the port village of Sa Calobra. HistoryDesigned by Italian / Spanish engineer Antonio Parietti and opened in 1933, Sa Calobra is a marvel of engineering. It was built entirely by hand, the 26 bends following the contours of the cliffs and based on the design of a neck tie. The 'knot' of the tie is represented by a 270 degree Spiral Bridge at the top of the climb. Interestingly, the road was one of the first engineered purely with tourism in mind. Cycle FactsSa Calobra is a Category 1 climb 9.44 km in length with an average gradient of 7% (12% max), rising 668 metres to a peak of 731 metres. KOM: Ed Laverack - 24:36 (Apr 28 2022) 378 average watts; 23.0 km/h average speed QOM: Mavi Garcia - 29:51 (May 30 2020) 19.0 km/h KOM (unofficial) - 22:30 (2012) Bradley Wiggins at Sky's Winter Training Camp before the Tour De France Victory. Need to KnowThere are only three ways to reach Sa Calobra and all pass the Coll de Reis - 2.6 km at 6% average gradient. 1. Coll de Femenia (Cat 2) - 7.2 km - 6% av grad - 407 m (heading west from Pollenca) 2. Coll de Sa Batalla (Cat 2) - 7.8 km - 5% av grad - 381 m (heading north from Caimari) 3. Puig Major / Soller (Cat 2) - 14.8 km - 5.8% av grad - 842 m (heading east from Soller) This makes Sa Calobra tough to ride to and it is an 'out and back' ride so expect a long, hard day in the saddle. Battling the Beast of ProvenceThe view from my Backroads 'Leader Training' accommodation in Provence is one, not just cyclists, but everyone will appreciate. Mt Ventoux casts its mighty shadow over the whole region, a mountain that stands alone, although geographically part of the Alps, at 1900 metres. Even its name 'Mt Ventoux' fuels the iconic status; 'Ventoux' meaning 'windy' in French, while the 'mistral' blows winds as high as 320 km/h at the summit. The limestone at this peak accommodates no trees or vegetation of any kind, creating a moonscape that can be seen for miles around. It should come as no surprise that cyclists flock in droves to this mystical mountain. The world's most watched annual sport, the Tour De France, has crossed Ventoux six times and has been used as a summit finish on ten occasions. The most famous of the three climbs, from the small township of Bedoin, takes pros over an hour and top amateurs 1.5 - 2 hours to ascend.  Approaching the Summit Approaching the Summit Scene of so many Tour dramas, Ventoux is carved into so many people's minds. In 1967, British cyclist, Tom Simpson, approached the summit weaving wildly across the road before crashing to the tarmac. Delirious, he asked spectators to put him back on his bike but just half a mile from the finish he collapsed and died still clipped into his pedals. Claimed by heat exhaustion from a combination of dehydration, amphetamines and alcohol, Tom Simpson was just 29 years old.. A memorial can be found near the summit. In 2016, due to high winds at the summit the day before the race, organisers shortened the climb by 6 km. Yet, even with the finish line further down the mountain, mayhem was to ensue. At the finale, a motorcycle induced a crash involving Bauke Mollema, Richie Porte and the Yellow Jersey Race Leader and current Champion Chris Froome. While Mollima and Porte were able to remount, Froome's bike was broken and he was forced to jog 100 metres up the mountain before grabbing a neutral service bike. However, being so gangly and tall, the bike didn't fit him and so the scene was set for the best rider of his era to cross the Ventoux finish line looking like an oversized clown.  The moonscape The moonscape Such stories seem to emanate from the bald mountain and I felt compelled to ride Ventoux's fabled slopes. I was keen to make three ascents from Bedoin, Malaucene and Sault and to become a member of the Cingles Club. I started from Bedoin, the most famous ascent of 21.5 km and 1610 metres at an average of 7.5%. The first 6 km are a good warm up and open but once in the forest the next 10 km are around 9-10% and very hard, yet very beautiful. The trees start to break and there is a transition to the famous lunar landscape where winds can really start to take a toll. I passed Chalet Reynard and enjoyed the last 6 km, stopping for photos and to pay my respects to Tom Simpson.  The view from the Summit The view from the Summit I was informed by others that the Malaucene road was covered in ice and too dangerous and so I decided to descend the 26 km to Sault. It had been cold at the summit but for the end of March it was surprisingly mild. In fact, the road to the summit is officially closed until mid May and it is necessary to duck under a barrier close to the top. When I started the climb from Sault, I was soon sweating under the sun. But this climb starts higher on a ridge and involves just 1220 metres of climbing at an average of 5%. My legs were more fatigued than I bargained for and I was now quite content with just finishing the two climbs. Once past Chalet Reynard, the Sault route joins the Bedoin ascent. Unlike the first climb, when the final 6 km seemed a bit of a relief, this time the road up had become steeper and I was far more aware of the gradient. I reached the summit the second time happy but relieved, and looking forward to a breath-taking descent. Mt Ventoux is everything I hoped it would be and being so close to my Backroads work base, a mountain I am sure to return to several times. Maulacene, a fourth ascent by mountain bike and a tandem attempt with my wife still await. I would recommend this climb to everyone - If the Bedoin ascent is too daunting then Sault is far more manageable. Days after, snow fell on Ventoux and its beauty and majesty was etched into my memory as I bid Ventoux and the stunning countryside of Provence a bientot.

Lands End to Accident & Emergency

The Riders & the Support Team Six riders were to complete the whole of the long, arduous journey of 861 miles (1400 km) journey from Lands End to John O'Groats, several with little or virtually no cycling experience at all. The Irish tandem of ex-Lion Rob 'Hendo' Henderson and David 'Patsy' Clein and the English machine of Peter 'Wints' Winterbottom and Paul 'The Big Bash' Bashir ground their way the full length of the British mainland. The Scots mainstay of Michael 'Goldie' was accompanied by Chris Gore, Rus Kesley, Craig 'Chick' Chalmers, Declan Goldie and myself, Phil '5 bellies' Welch, and the Welsh started with Rhodrie Mcatee and '5 bellies', were assisted by Declan Goldie and later piloted by Alan 'Walshy' Walsh. The Scots were to claim the most stage victories but considering the fact that it took 6 riders to do it (4 more than the permitted 2) and the Welsh tandem, which mopped up the most King of the Mountain points, was barely Welsh other than in name (and was off the road on stage 5), then overall victory should surely go to the Irish and English tandems. Never was there a more modern tale of the tortoise overcoming the hare, the Irish and English grinding slowly and purposefully to ultimate victory. Moreover, none of us would have made it at all without the tireless work of Ant and Dec who ensured we navigated the right roads, supplied us with regular nourishment and regularly fixed the broken spokes of the 250kg Irish tandem. The Journey Blessed by the Gods of Rugby, the 10 day journey from Lands End to John O'Groats could not have been completed in much better weather. Leaving Cornwall on the 15th September, with an average temperature of 15 degrees, the peloton of four tandems missed the storm that would sweep across the south of England the following day. Admittedly, at the Severn Bridge, the high winds forced us into a one mile trudge into Wales. Beautiful scenery then rolled by until we travelled through the invidious towns of Warrington, Wigan and finally Preston. The wind was now blowing hard and further north the M6 motorway was closed and the trains to Lockerbie, Scotland had stopped running, leaving Wednesday night commuters stranded in the north west. A day earlier and our stage from Preston to Carlisle would have been aborted. The next day we rolled through the beautiful Lake District Hills where we got our first real soaking in the final 50 km of the day. However, the sun was to embrace us as we rolled across the border into Scotland, onward to Edinburgh, traversing the idyllic Cairngorm hills, past the ski runs of Aviemore and into Inverness. Crossing the Forth Bridge, the cool but amicable weather continued as we finally made our way to our final destination of John O'Groats. The Cameraderie Without doubt, this is one experience that will be forever etched on the memory. Nevertheless, meeting the guys in a 1st class carriage on a train from Paddington to Penzance was a slightly disconcerting experience. After all, some of these guys were my heroes in the 80's. I was handed a mojito from a bag containing a mountain of alcoholic beverages as the others drank copious amounts of beer and other cocktails. These were players from an era before rugby became professional after the 1995 World Cup and rugby and drinking were inexplicably linked. Later, in a pub in Penzance, I was introduced to the three basic drinking game rules and I was soon downing my first pint. Frivolities continued into the small hours of the morning but I was able to slip away at around midnight. I feared it would not be the cycling but the drinking that would be my downfall. Fortunately, the drinking abated once the cycling began, but returned with vengeance on the final day. Some of the boys had really suffered throughout the trip. My original partner, Rhodri finally succumbed on Day 5 to the injured shoulder he had damaged playing rugby the day before we started. Others such as Hendo, Patsy, Bash, Goldie and, I suspect Wints, although this guy is a rock and never ever complains, had severe aching posteriors, so much so that Hendo would often burst into the words of Johnny Cash 'cycling is a burning thing, and it makes a fiery ring'. With the cycling finished, we returned to the bus and the beer and whisky flowed freely, as DJ Bash pumped out the music from the 70's. We stopped at another whisky distillery and ample amounts of aged whisky was drunk. The bus was pumping and I was reminded of my days travelling to and from rugby games across the north of England with East Leeds Rugby League (RL) and the whole of the country with Loughborough University RL. We picked up an Australian hitch-hiker and, despite their initial reservations, they joined the drunken party. Walshy was dancing Gangnam Style on the road when the bus stopped at the lights and Hendo was in particularly good voice. At the hotel, Hendo presided over court proceedings and drinking fines were dished out. The American tourists in the bar joined in with the fun and we all stood for a powerful rendition of the star-spangled banner. I arm wrestled big Walshy and lost, he arm-wrestled Bash and lost and then repeated the defeat on the other arm, the hotel cut our access to more drink, Walshy later jumped down a flight of stairs aiming to rugby tackle Dec but missed, putting out his back in the process. I was comatosed by 6pm, later to wake up to the predictable smell of vomit! Lessons Learnt Overall, this was an experience that I would never have missed. While I didn't suffer from aching legs and the discomfort of saddle sores from the long days in the saddle, I did have to take pain killers for the first 5 days for an infected root canal from where I lost my tooth a few weeks previously, eventually seeing an emergency dentist in Carlisle for antibiotics; I also tore my bicep off my shoulder from the arm-wrestling, resulting in a trip to A & E when I returned to London, and forcing me to carefully nurse my arm for at least 6 weeks. Regardless, cycling the length of the British Isles on tandems with a fantastic bunch of guys was an absolute pleasure both on and off the bike. Despite their heady status as top rugby players, they are a great bunch of intelligent, fun-loving guys with massive hearts, doing their utmost to help their good friend Doddie Weir, raise money for MND. Please feel free to help me raise money for this wonderful cause, to assist those suffering with this terrible disease and hopefully to find a potential cure.

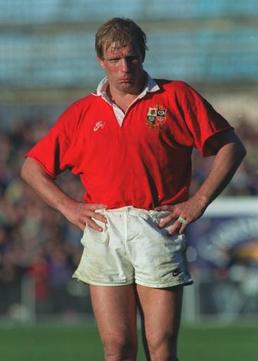

Land's End to John O'Groats: 10 days, 1386 km, 13,209 m The Doddie’5 Ride LeJog* was conceived by Rob Henderson, ex Irish and British and Irish Lion, in the early hours of the morning in a pub in London. It seemed like a good idea at the time as an event to support Doddie Weir in his fight against Motor Neurone Disease but with the 10 day, 900 mile cycle looming ever closer Hendo wishes that he hadn’t been quite so ambitious. The challenge will be attempted by 4 tandems each representing the four home union rugby teams. Hendo leading the Irish challenge, Craig Chalmers the Scottish, Peter Rogers the Welsh and Peter Winterbottom the English. It is not a race but I’m sure there will be plenty of competition over the 10 days, especially in the bar area trying to keep up with Hendo. *The LEJOG cycle ride is the grand daddy of all cycling challenges in the UK, starting at Land's End in Cornwall (the extreme southwest point in mainland Britain) and ending at John o'Groats in northern Scotland - very close to the most northerly point of mainland Britain. My Name'5 Doddie Foundation Motor neurone disease (MND) is a rare condition that progressively damages the brain and nervous system. It's caused by a problem with cells in the brain and nerves called motor neurones, which gradually stop working over time. This leads to muscle weakness, often with visible wasting. It's always fatal and can significantly shorten life expectancy, but some people live with it for many years. There’s no cure, but there are treatments to help reduce the impact it has on your daily life. It mainly affects people in their 60s and 70s, but it can affect adults of all ages. George "Doddie" Weir, one of rugby’s most recognisable personalities, is a Scottish former rugby union player who played as a lock, making 61 international appearances for the Scotland national team. An excellent lineout specialist he was selected as part of the British and Irish Lions tour of South Africa in 1997. Weir was famously described by legendary commentator Bill McLaren as being "On the charge like a mad giraffe". In June 2017, the Scot revealed he was suffering from Motor Neurone Disease. From the outset, Doddie has been driven to help fellow sufferers and seek ways to further research into this, as yet, incurable disease. In November 2017, Doddie and his Trustees launched the registered charity My Name’5 Doddie Foundation:

With your support, you will help Doddie and the Trustees make a difference to the lives of those coping and battling with Motor Neurone Disease.

Craig now lives in Esher which must mean he is a stockbroker so will have ridden the Surrey Hills andtamed Box Hill in training for this Doddie’5 Ride LeJog event. Craig has 166 points for Scotland but is perhaps most famous for his 3 penalties against England in Scotland’s 1990 Grand Slam success. We expect Craig in his lycra kilt, to be leading from the front of his peloton and to be refuelling on McEwan’s super strength lager whilst munching on a deep fried Mars Bar at the designated feed stations. That’s enough stereotypes hit there me thinks.

The Route Sunday 16th Sep: First Day – Land’s End to Okehampton (103.95 miles, elevation: 6785ft) Monday 17th Sep: Okehampton to Bristol (107.90 miles, elevation: 4643ft) Tuesday 18th Sep: Bristol to Shrewsbury (101.50 miles, elevation: 6722ft) Wednesday 19th Sep: Shrewsbury to Preston (88.30 miles, elevation: 3219ft) Thursday 20th Sep: Preston to Carlisle (93.14 miles, elevation: 4305ft) Friday 21st Sep: Carlisle to Edinburgh (89.60 miles, elevation: 4000ft) Saturday 22nd Sep: Edinburgh to Blair Atholl (78.49 miles, elevation: 3586ft) Sunday 23rd Sep: Blair Atholl to Inverness (79.94 miles, elevation: 3487ft) Monday 24th Sep: Inverness to Lybster (88.50 miles, elevation: 5475ft) Tuesday 25th Sep: Final Day – Lybster to John o’Groats (30.02 miles, elevation: 1117ft) Join in Come and join the Peloton for a day and give your support to the My Name’5 Doddie Foundation. Pledge £150 to the charity and spend the day in the Peloton. Just email [email protected] for further details. Donations Please kindly donate to the My Name’5 Doddie Foundation, raising funds to aid research into Motor Neurone Disease

Lest we forget: A Perfect Weekend of Racing, Culture, Camaraderie, Dining & Sunshine With over 70 years of World Peace, very few of us have been directly affected by the horrors of a world war and we must never forget that so many people sacrificed their lives to provide us with the freedom and opportunities that we so often take for granted in today's world. No amount of suffering we put ourselves through will ever match the absolute horror these young men and women had to endure - Lest we forget. It is impossible to not be affected by the rich history that embraces you when arriving in Abbeville, located on the River Somme. Our wonderfully quaint Bed & Breakfast was nine kilometres east, in the picturesque village of St. Riquier, opposite the British Cemetery for casualties from both the 1st and 2nd World Wars. Littered with historical attractions and incorporating a stunning landscape, the route of the Ronde Picarde takes riders through the heart of the Bay of the Somme. Initially heading inland from Abbeville before turning for the coast and the Bay of the Somme and the climb of the 'la Bosse de Long', the route returns inland past lakes and battlefields towards the finish at Eaucourt sur Somme. Despite being extremely flat, weather conditions (heavy rain and strong gales) last year made riding extremely challenging and it was the first time I had experienced racing in echelons to shelter from the winds as we crossed the vast Normandy plains. Despite the atrocious conditions, my mates and I had thoroughly enjoyed the experience and we were back for a second assault on the Ronde Picarde. The sun was shining and there was a mere breeze - this was going to be fast. Released to the heart-thumping sounds of Metallica's 'For Whom the Bells Toll' Jay, Dean and I were surfing the wheels at over 40 km/h, working our way out of Abbeville, while avoiding traffic islands and slower moving riders. Graham was enjoying the chaos far less and witnessed a crash close by but generally the groups started to form not long after the road narrowed for a bridge crossing on the town outskirts. The first few climbs were to further re-organise the mass of carbon, aluminium and flesh into more orderly pelotons of which Jay had placed himself into the front, while Dean and I were in one following, and Graham in a group not too far behind. In these types of events it is critical to keep a careful eye on your position within the group. My intention was to stay towards the front and not allow myself to drop too far back. Every time we took a corner, riders would need to accelerate powerfully to stay in the wheels and the further back, the more extreme the acceleration. Furthermore, on a couple of climbs, I could feel myself slip back a little so I tried to ensure I would still have others nearby to help me back towards the front. A moments lapse in concentration, and I slipped off the back on a longer climb and I found myself isolated. Fortunately, I was swept up by a small group of team riders and I was soon safely ensconced back in the peloton. As we hit the Bay of the Somme, a sharp right led us onto the 'la Bosse de Long', a short but steep hill, where a decent amount of locals cheered us on. The first of two feed stations was passed after 95 km, and Dean stopped for water and had to start a 30 km chase to get back to our peloton. Feeling smug that I hadn't needed to stop and was thereby saving precious energy, I came to a large roundabout at the 106 km mark where the shorter Medio route turned off to head back to Abbeville. The riders around me turned right and I followed before realising I should have carried straight on. I stopped, turned round but the group had already disappeared up the road. At first, I was virtually alone but desperate to catch the group I initially worked with a rider, who was already suffering and had very little to give. Fortunately, not long before my first ally dropped off, we were joined by a Dutch rider who was much stronger. I could see Dean ahead who was also tantalisingly close to getting onto the group but never quite making it. I wished I could radio him back so we could work more efficiently as a group of three. It seemed like an age before he spotted us and sat up. We then worked together and as we started to chip away at the gap, it was decided to make a concerted effort to re-join. The deficit closed but I was now on my absolute limit; apparently Dean was too (his heart rate hitting a new max of 184). I needed 20 seconds more effort to reconnect but then the lights went out as my heart seemed to explode. My allies were back on but I just slipped back - had I lost my chance? Fortunately, a group of 5 riders came past me, I managed to jump on their train and the catch was finally made. Back in the group, my major physiological signs normalised again. It's amazing how much faster and easier it is to ride in a large group. Dean and I were now so comfortable that we were keen to go even faster. But any sustained effort to move ahead of the group would ultimately be reeled in by the chasing pack. Jay and Graham were experiencing the same feelings in their respective groups. It was not until we hit the last climb of any note, just outside Abbeville, that the group disintegrated. Around about 12-15 of us forged on to the finish. Dean and I crossed the line together to find Jay already tucking into his post race meal. As we did the same, a smiling Graham emerged from beyond the finish line. We had all exceeded our expectations for the race, all far quicker than the previous year. Roll of Honour Jay Baskerville - 5.04.15 - 37.7 km/h Dean Turner - 5.28.57 - 34.8 km/h Phil Welch - 5.28.57 - 34.8 km/h Graham Cheeseman - 5.46.58 - 33.3 km/h This weekend is a must for anyone looking for a late-season race goal. But it's not just about the race. The village of St. Riquier is beautiful, the accommodation exceptionally comfortable and our French hosts extremely friendly. After we had raced, we took in the drama of the local criterium race lapping 40 times around the village and finishing each lap up a cobbled climb, then tucked into a delicious three course meal of frog's legs, steak, ice cream, beer and red wine while absorbing the talents of the 'French' country and Western dance troupe. The following day we took a pleasurable ride to the beach at St. Valery sur Somme before finally heading home. Without a doubt, this is an event that many of us have already entered into our diaries for 2019. In Loving Memory of Rowena Stevens

“FIENDISHLY SIMPLE, YET BRUTALLY HARD. EVERESTING IS THE MOST DIFFICULT CLIMBING CHALLENGE IN THE WORLD.” The concept of Everesting is fiendishly simple: Pick any hill, anywhere in the world and ride repeats of it in a single activity until you climb 8,848m – the equivalent height of Mt Everest. Our Everest challenge meant riding 60 reps of Toys Hill in Kent, which has an average gradient of 5% over three km, covering a total distance of nearly 380km’s and we planned on taking around 17-20 hours. Robb Cobb had mentioned his desire to do this over 6 months ago but planned on doing it solo believing no one in their right mind would possibly consider joining him. Wise thinking, but he hadn't taken into account the collective insanity of other riders in our training group. Jay Baskerville, thinking of putting in some solid hill training before taking on multiple ascents of Mt Ventoux, then brought up the idea of Everesting on 11th August, just two weeks before. I instantly agreed to it and Andrew Gleeson's initial reaction was 'no way, that's just mad'. Just a couple of days later and he was coerced into it and some fast-tracked planning was set in motion. Four lunatics from the Bigfoot Cycle Club would Everest but we would all be doing it for a number of worthy causes. I would be fundraising for CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably), a charity aimed to help reduce the number of suicides in the UK to people far too young. After almost perfect weather leading up to the event, severe thunderstorms hit the day before and 'Toys Hill' was suddenly deluged in torrents of water. Robb, happened to be visiting the 'Fox and Hounds', the pub at the top of the hill where we would have our support crew and he reported that in two spots there were rivers crossing from one side of the road to the other, streams running down on both sides, various large pools of water and a fair bit of debris. Fortunately, the rain abated in the evening but we now knew that the descents would be far more treacherous and the chance of mechanicals and punctures had substantially increased. Jay, Andy and myself arrived bleary eyed at the Fox and Hounds pub at 1.30 am, only to find Robb, doing his own thing as usual, had already completed two laps of the hill. Confirming our worst fears, he told us the tarmac was badly potholed at the top, there was still a lot of stones and small rocks on the road and so extreme caution would have to be taken, particularly on descents. Despite the warning, on the very first descent I hit a large pothole and lost my water bottle; clearly not learning my lesson I hit it on the second descent and, with a loud crack, my rear wheel rim was shattered, forcing me to trudge despondently back up the hill, wondering if this event was meant to be. Close to the top, Jay and Andy overtook me and quickly fetched my heavy back up wheel from the support vehicle. I was up and running again but the wheel was clunky and the rear braking almost non-existent. Incredibly, I hit the same pothole on my third descent and on retrieving my water bottle, I found another (which I found out later to be Robb's), safe in the knowledge that I wasn't the only one to have hit this hole. Indeed, on hitting this, Robb had flatted his rear wheel and broken his light mount, leaving him to descend at over 60 km/h, holding the light in one hand and the rear brake with the other. With this precarious set-up, Robb flatted twice more in the night. The daylight broke through after 5 am, and it was a relief to be able to see more clearly, particularly while descending. Surely, this would be so much easier now and the worst of the mechanicals would be behind us. The warmth of the day was starting to break through as we rode towards 9 am, when suddenly my front tubeless tyre exploded, possibly catching the edge of a drain or a sharp rock. I fitted a tube but half way up the climb the tube squeezed through the split tyre wall and blew, leaving me to walk to the top again. I had done 20 laps (a third of the required distance) and after assessing my options, Jay kindly gifted me use of his Planet X EC-130, Cycling Weekly's Aero Road Bike Of 2017 Award Winner. Luckily, Jay and I are both vertically challenged and so very little needed to be done to fit me to the bike apart from a quick pedal swap and an inch off the saddle height. Meanwhile, Andy had punctured three times and Robb is heard muttering that he is about to throw in the towel. Andy reminds him that his brother, Mark Gleeson, is out emptying a local bike shop of inner tubes and CO2 cannisters, that we were all struggling through some adversity, and the show must go on. Robb gets back to Everesting. This day would have been so much harder and not nearly as bearable without the support of riders from Bigfoot, several friends and our marvellous pit crew. During the morning, a tsunami of blue and white swamped Toys Hill and helped us up several ascents. It was heart-warming to pass multitudes of riders shouting our name and offering encouragement. So many people came out to support us and I thank you all. In particular, I must thank Chris Bell, who rode six laps with me and took me to 30 laps and half way, and almost immediately he was replaced by Richard Collier, who rode ten laps and took me two thirds of the way through. Graham Cheeseman, Myles Davidson and, as night approached again, Rus Kesley, all put in big shifts. Mike and Mark (Andy's dad and brother) were absolute legends and provided bottles and food every lap, charged lights and batteries, as well as so much more - just seeing a supportive face every ascent filled us with the desire to continue and we wouldn't have been able to complete this challenge as quickly and successfully without them. With the sun sinking behind the trees, we are finally left to our own thoughts, the camaraderie of the past few hours an almost distant memory. The road falls quiet except for the occasional car returning from an afternoon excursion or shopping run. This time was mentally the most difficult, even if it wasn't as challenging technically as the night descending. Interestingly, nutrition strategies clearly differed between us. Andy and Jay are lapping faster and staying together but are taking longer stops and eating proper food; Robb is also stopping for a short break and sandwich after every five laps, while I stay on the road eating primarily gels and consuming protein and carbohydrate drinks. Although I am lapping more slowly, I manage to close the gap on the others while they enjoy time off the bike. In truth, I feared that any time off the bike may have dissuaded me from getting back on, so I just kept turning the pedals, just like I would have done if I was competing in a 24 hour solo race. Ironically, the only occasion I did stop to eat food, a slice of Robb's wife, Annie's delicious Millionaire Shortbread, my top front tooth broke off, leaving a gaping hole in my almost non-existent smile. We had hoped to have finished before darkness enveloped us again, but the early mechanicals had long scuppered that hope. Furthermore, Robb had suffered even more trouble, when his rear derailleur had somehow become twisted with his chain, initially thought his ride was over, but patiently disentangled the drivetrain. At around 8 pm, we were all riding with lights again, and so speeds on descents, which had ranged between 60 and 85 km/h in the daytime, were now much less impressive, the spectre of the unseen potholes looming again. But we had learnt the layout of the road and surely they wouldn't trouble us again. Amazingly, we all appeared to be on the same lap, and so we completed the last few laps together at a more serene pace. Then Robb disappeared from our group, a victim of yet another puncture. We completed the 60th ascent without him, waited for him at the top and with fuzzy brains and poor maths we agreed to do one more lap, just to be sure we had covered the necessary 8848 metres of climbing. Once again, Robb failed to follow the script, perhaps not willing to risk another descent in the dark, and did it 'his way', riding just half the hill again while Jay, Andy and I completed the 'glory ascent' together. 390 km, over 9000 metres of climbing and 21 hours total elapsed time and it was finally over... Although this is definitely a tough challenge, one that only 2200 people worldwide have completed, the discomfort is only temporary and it is our own choice to participate. My heart goes out to those who suffer pain and suffering every day, so much so that they often consider taking their own life. My niece was one of these and we must do more to listen and help as much as we can. By undertaking this challenge, I hope that this endeavour can help raise awareness and financial support to those poor young people that are suffering daily. I have set up a 'Just Giving' page to raise money for CALM, while other charities we were supporting were the Hearing Conservation Council, the National Association for People Abused in Childhood, Bromley Mencap and Freddie Farmer. Please give generously to help others considerably less fortunate than ourselves.

Shake, Prattle and Roll - The story of 3 Bigfoot Riders (and a rugby legend) at London's Biggest Sportive 27,000 lucky riders took part in the 6th edition of the Prudential RideLondon-Surrey 100 (more than 80,000 applied), an event conceived after the 2012 Olympics and which has raised more than £53 million for charity since 2013. The 100 mile Sportive is ridden on the same closed roads as the professionals, winding its way past several historical London landmarks and incorporating the stunning Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Beauty. Bigfoot Cycle Club in Bromley, South London was well represented. Among their number was Jay Baskerville in the very first wave, I was in the third and Lance Welch was over half an hour further back. A three am alarm call had roused me from my short sojourn into that night's land of slumber and I was lined up at 5.40 am in pleasant early morning temperatures in basic race kit. A house move had left me a bit disorganised and I had neglected to wear my base layer; the forecast was for heavy rain but not until 10 am and I would surely be almost finished by then, a time of 4 hours 30 a distinct possibility. I would need to average just under 37 km/h but with a fairly flat course and fast moving trains of riders this would be fine - so long as the weather followed the script. At the starting gate, Jay had taken a photo of us and tagged it on Facebook with the line 'ready to roll'. But his story was more 'rock' than 'roll'. He got off to a flying start at 5.44 am to the sound of the loudspeaker playing 'Highway to Hell'. AC/DC's Lead Singer, Bon Scott must have known more about today's events than Jay could ever have imagined. I left eight minutes later to the booming bass of indoor training classic 'Sandstorm', while I gather the loquacious Lance left to the loud crack of a thunderstorm. The first 20 km were covered in an average speed of 40 km/h as I was lucky enough to jump aboard the 'bullet train'. We were soon passing riders from the first two waves who would have been better suited to the last two waves and merely formed slow moving road furniture. It seemed weird to be hurtling through red lights in the heart of London and to have the whole road to ourselves - at this time, we only needed a small streak of tarmac of 2 bike widths although I'm sure the hordes of riders following would be devouring every inch later on. Jay was ahead doing much the same, although he was still being held behind the lead car and would be for the first 60 km. Lance was freelancing a number of groups endeavouring to find the magic key that would unlock the door to the train that matched his personal pace. We flew through Richmond Park at speeds often topping 45 km/h and I noticed the third of twelve water stops flash by. We shot through Kingston, barriers to hold the spectators at bay but, at this time, very few souls were around. When we passed Hampton Court, the weather was turning colder and rain was now falling harder. Pools of water would wash more and more debris into the road, particularly after seven weeks of continuous hot, dry weather. Stranded riders fixing punctures were becoming more commonplace . I was running tubeless and felt smug in the knowledge that this set up was much more reliable in these conditions. Jay less so. Sixty kilometres and he had punctured and was off the front - was it some sort of karma. Shortly before, he had been engaged in a heated argument with another rider whose saddle bag contents were emptying dangerously onto the road; giving rise to Jay dispatching some uncharacteristically colourful expletives. The puncture quickly fixed, he fell back into the second wave only to puncture again. The CO2 cannister used to inflate this tube caused it to explode and he now needed to flag down another rider for a spare - the tube he received had been previously patched and with little confidence he was back on the road, jumping from group to group to make up for lost time. Entering the Surrey Hills, Newlands Corner brought the first climb of any note, the average speed dropped and groups began to disintegrate. Lance is initially dropped and then struggles in the rain and gusts of wind blowing up to 55 mph as cornering on descents becomes dangerous, almost terrifying. Fortunately, he recovers quickly as his endurance starts to kick in and he is back literally surfing through faster and faster waves of riders. Jay uses Newlands Hub to buy a spare tube and inflate his tyre back to racing pressure. I pass through the stunningly picturesque village of Abinger Hammer before ascending the day's biggest climb, Leith Hill. The rain is now relentless as the town of Dorking 65 mile in, comes and goes. As I approach Box Hill, Jay comes past bemoaning his luck, but soon he has gone leaving me to soldier up Box, a hill the men rode no less than nine times during the 2012 Olympic Road Race. The precipitation worsens but as the route flattens, trains reform and the speed returns to around 37-40 km/h.

Meanwhile, I was working with a small group but as we went through Kingston for the second time, the small crowd that had braved the incessant rain suddenly witnessed a bike come crashing down heavily on a sodden corner. I was following closely but just managed to avoid riding over the top of the stricken rider. I later found out that there had been a number of considerably more serious crashes further back, causing diversions around both Leith and Box Hill. After a small climb through Wimbledon, we are soon riding beside the Thames. I was feeling extremely cold and began shivering; clearly that base layer and even a gilet had been a necessity. I hadn't eaten or drunk anywhere near enough and I was struggling to stay with the same riders I had ridden with for the final 20 miles. I finished in a bit of a daze and immediately after finishing on The Mall, in front of the majestic Buckingham Palace, I started to shake uncontrollably, the cold biting deep into my bones. Elsewhere, Jay had punctured a fourth time at Albert Bridge, on the Embankment. This time he helps another rider who had punctured but was without any tools. As he remounts, Jay gets 500 metres before the tyre flats again. He is at Lambeth Bridge, 2km out and decides this is enough, stops his Garmin and, allegedly, is last seen jumping into the Thames. Lance, who had dropped Martin Johnson when he too had suffered a puncture, was finishing fast. Sitting in third wheel behind a strong rider who was burying himself at the front, he plans and schemes his explosive Cavendish-esque finish. Even at 29 mph he is unable to come round the man who had dragged him for at least 2 miles but Lance proudly manages his pre-race goal of sub five hours. Undoubtedly, the London Prudential is an incredible event which is certain to promote cycling as a sport and as a recreational activity for all levels and ages for years to come. The closed roads combined with a spectacular route through London and the Surrey Hills makes this a bucket-list event. This year was made much more challenging with the heavy downpours, high winds, treacherous road conditions and numerous punctures but it was a wonderful experience and one I'm sure myself and many others are destined to repeat in the future. Roll of Honour

Back to Slay the Dragon - A modern-day Legend of Treachery and Heroics The Dragon Devil is one of the most iconic sportives in the UK (returning for its 15th year in 2018), and offers the perfect representation of the world’s most famous cycle event, the Tour de France. Riders can choose to ride the Gran Fondo (223 km); the Medio (153 km); the Macmillan 100 (100 km) or the Dragon Devil (300 km). There's even a 3 day tour which takes place over 2-3 days, finishing with the rider's choice of distance on the Sunday. Far and away the hardest road event I have done to date was the Dragon Devil in 2017. The 300 km of riding are punctured with a combination of long and steep climbs, totalling a massive 5000 m of vertical ascent, and with Wales throwing in dreadful weather conditions of strong winds, incessant rain and even hailstones, I really suffered last year. However, as we lined up at 6.30 am to start the event, the sun was shining, the sky was clear and it was already warm. This seemed like a perfect day to 'slay the dragon'. A group of around 25 riders from the first wave were setting a decent pace at the front as we motored towards the first climb of the day - the Bwlch. There appeared to be a large patch of broken glass on the road and we took evasive action attempting to avoid it. Shortly after, I heard hissing and a rider in front of me pulled over with a suspected flat, while my Bigfoot team mates, Jay and Cassie stopped suddenly to fix punctures. There was confusion in the group as more and more riders pulled to the side of the road. I looked down at my front wheel and it was glistening in the sunlight. I stopped to find ten drawing pins in my front tyre and four in the rear. It soon became apparent, the event had been sabotaged by a mindless minority. I quickly extracted the multiple pins out and replaced the tubes, while Andy patiently waited beside me, both of us being bitten by a plague of midges. We rolled back out to start the climb, riders strewn everywhere fixing punctures. With only 2 spare tubes, which I had now used, I needed to get to the first feed station 34 km away to replace them. Riders were still puncturing and so it was necessary to keep a watchful eye on the road ahead. Unfortunately, it wasn't long before my front tyre lost air and I was on the side of the road again, preparing to patch the new tube. Ross, a client from my Wattbike classes, saw me and quickly passed me one of his spares. I fixed the third puncture and then climbed and descended the Bwlch and Rhigos without further incident. I was still not at the feed station when my rear tyre lost air and I was stranded again. A group of guys from a club in Beckenham stopped immediately and generously provided a fourth tube and co2 gas cannisters and waited until I set off again. The wheel was bouncing as the tube was bulging to the side and so the same guys helped locate and solve the problem and I was back on my way. When I arrived at the feed station, all the spare tubes had been bought by other riders and so I would have to ride another 37 km, hopefully without further incident, before I could get spares. Furthermore, guys from Bigfoot, who had started an hour behind me, had also reached the first feed station, emphasizing how much time I had lost - perhaps this was going to be another victory for the Dragon. I contemplated another tough, and overly long, day in the saddle. Whatever goes up must come down. Despite the large amount of climbing, the descending had been absolutely exhilarating - at one point, at the bottom of a long, sweeping downhill a rider turned to me grinning and exclaimed how brilliant the last descent had been and I couldn't agree more. The sun was shining, the temperature warm and I was thoroughly enjoying myself again. As we climbed the Devil's Elbow, Didi the Devil appeared on a 20% switchback, jumping up and down at the side of the road with his pitchfork and red tights and thoughts of suffering legs temporarily vanished. Over the past 25 years Didi has become one of the Tour de France's most recognisable sights but this experience is no longer reserved for the professionals. With 96 km gone, I was finally able to buy a couple of spare tubes and I was on my way again. With so much time lost I was just going to enjoy the day but it was becoming harder to find allies to ride with. I would connect to a train but the climbs seemed to eventually shed them and I would then need to forge ahead to the next group. Suddenly, on a long climb I saw one of my teammates, Cassie, at the side of the road. I stopped and, knowing the next feed station was not too far away, I managed to get Cassie to follow my wheel up a series of hills, working hard to hold a fast enough pace for Cassie to follow. The feed station revived spirits and, as we were leaving, we were joined by a couple of members of Team Yorkshire, including Joss, a member of my Wattbike classes. We worked well together but after a couple of short, punchy climbs, Cassie dropped back, content to hold her own pace. Soon after, those doing the Gran Fondo (230 km) route peeled off and our group shrunk further. Four of us descended into a small village and towards the next feed station. However, the other guys were held up by traffic and so I forged on alone. I decided to forgo the feed stop and rode predominantly solo until the next big climb, the Devil's Staircase. The Devil's Staircase, deep in the Welsh wilderness, quickly ramps up to 25%, levels slightly then ramps up again. It is some time before you reach the top but one of the highlights of the Devil ride awaits. Last year, at this same point I was hit by hailstones and high winds. This time, however, there were clear skies and stunning views of Llyn Brianne far below. This beautiful reservoir sits at the head of the River Towy, its dam the world's largest clay core dam in the world, built in 1968 and holding 62 million tonnes of water. I drank in the sensational views and then enjoyed the steep descent towards the valley below. Undulating through several pine forests, the route finally worked it's way down, where I joined a group of strong riders keen to keep pushing a fast pace. The drink stop shown in the road book never materialised but despite a lack of water, the work rate in the group was high and the kilometres ticked off quickly. At 219 km, we pulled in to the penultimate feed station and took on more water. Like many others, my feet were hurting in the heat but I was keen to keep moving and not wait for others. I was joined some kilometres down the road by three members of the last group I had been in and the pace picked up again. Climbing Black Mountain split us up but we re-grouped on the descent and at 256 km, we swept by the last feed station, which would have been an unnecessary break to our rhythm. Our team of four became two as we hammered the last two smaller climbs, passing many groups and riders from the Gran Fondo. We finished strongly, swapping turns and riding on our limit to the very end. We crossed the line together, nothing more to give. My second experience of the Devil was certainly memorable if not quite the stuff of legends. On the one hand, the worst of people came to the fore at the start of the event with the mindless tack attack. Indeed, the Dragon Devil promises entrants a 'Tour De France' experience. In 2012, defending champion, Cadel Evans and around 30 other riders were victims of a spectator tack attack. I fear this was not the type of experience the Race Organisers had in mind! On the other hand, I feel it only appropriate to focus on the generosity and camaraderie of the riders who helped me during my difficult moments with the punctures. Without their willingness to help, offer tubes and co2 cannisters and even wait and ride me back into the event, I would have really suffered. With their assistance, I was still able to finish 27th overall, in a time of 11:44:51 (10:51 moving time), an average speed of 27.6 km/h and barely an hour behind the winner. It's at times like this that it is an honour to be part of the cycling community. Bigfoot Role of Honour Dragon Devil (247 riders): Andrew Gleeson 21st Overall 11:36:47 Phil Welch 27th Overall 11:44:51 Cassie Baldi 81st Overall (2nd Female) 12:46:36 Gran Fondo (1207 riders): Dean Turner 79th Overall 8:24:50 Graham Cheeseman 135th Overall 8:51:30 Edward Wardill 165th Overall 9:00:41 Dragon Devil XL Jay Baskerville 1st 13:04:21 |

Author

Categories

All

Stage Races

24 Hours 7 hour Enduro Series 12 hour Enduros 6+6 hour Enduros Archives

August 2021

|

| CycoActive - Professional Endurance Cycle Coaching |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed