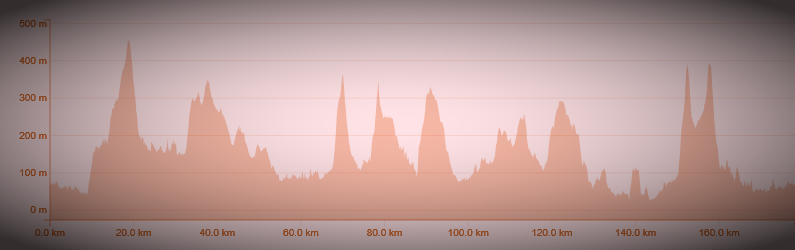

Jump aboard the Three Stop Pain Train The Tour of Wessex in the biggest multi stage sportive in the United Kingdom and has been serving up competitive cycling in the quintessential English countryside since 2006. Each stage provides a unique mix of challenging, yet stunningly beautiful terrain, timeless history and ancient monuments. The event attracts riders of all levels and offers the standard 3 day route of 523 km (325 miles), a medium 3 day route of 355 km (221 miles) or the chance to participate in individual days ranging from 102 to 127 km (64 to 79 miles). Historically Wessex is one of the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, whose ruling dynasty eventually became kings of the whole country and its land approximated that of the modern counties of Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, and Somerset. The region also figures prominently in the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and where English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy set much of his work. Stage 1 - 161 km - 1,900 m Stage 1 would take us from Langport, Somerset through Wiltshire and back to the event HQ. For the first stage, I was joined by my Bigfoot training partner, Robb Cobb, and we lined up in the first group to be released from the start. The weather forecast was for rain and storms but it was still quite warm. Ten minutes before setting off, the clouds burst and it became suddenly very cold and we were left wondering whether a light race gilet was going to afford enough protection. The peloton set off at a ferocious pace as early race nerves seemed to dictate and perhaps there was a desire to ride out of the driving rain. I looked for Robb but he hadn't made the front group. I found out later, that he had been caught behind a guy who was unable to clip in and despite almost closing the gap to the lead group he didn't quite make it. I was enjoying being pulled along at almost 40 km/h but suddenly just before the start of the Cheddar Gorge climb around 35 km in, I slipped off the back having left too large a gap - I worked back on a couple of times before the elastic snapped and the peloton was gone. Left alone with no one behind, I climbed the stunningly beautiful limestone gorge in the Mendip Hills. The gorge is the site of the Cheddar show caves, where Britain's oldest complete human skeleton, Cheddar Man, estimated to be over 9,000 years old, was found in 1903. It is easy to see why this popular climb was voted one of the UK's top 10 cycling roads. It is certainly not the hardest climb, at around 4% for 4 km. Nevertheless, I was glad I didn't have to race up it and started to see some benefit to being dropped. I was eventually joined at the top of the gorge by a fast moving group of four riders and, soon after, the rain abated. By the time I reached the next big test, King Alfred's Tower, 85 km in and with short ramps of around 30%, the rain had stopped and had been replaced by warm sunshine. Despite this, wheels were still slipping at the top of the climb. But this was the final test of the day, and we motored through the descents and flatter rides towards Glastonbury. I was joined, near the end, by George Lewis, a friend I'd met on the Marmotte in 2017, and we finished the stage together. I crossed the line in 60th overall (30 km average) with Robb just seven minutes behind. Stage 2 - 191 km - 2,300 m Lining up for Stage 2 and we were again given an early drenching by heavier rain than the day before and the prospect of storms all day - several people huddled under marquees until the last moment and apparently around 15 people rode to the end of the carpark before turning round and calling it a day. This time, the start was far more sedate, perhaps those early 'race' nerves had gone and spirits had been tempered by the rain. A small group escaped off the front of our peloton, but the main group stayed together as we rode towards Swanage in Dorset and the Jurassic Coast, England's first natural UNESCO World Heritage Site. There seemed to be a large number of riders puncturing in the wet conditions and the group started to thin down to around 20 riders. We were climbing, when I suddenly noticed sealant spouting from my front tubeless tyre. I watched intently, desperate to see the hole seal as I didn't want to lose the group. Fortunately, the sealant worked its magic and very little air pressure was lost from the front tyre. I was still in the game. We passed the ruins of the 11th Century Corfe Castle, built by William the Conqueror, and one of the earliest castles in England to be built at least partly using stone rather than earth and timber. Our group was dwindling, and with 8 riders remaining, it was time to stop at the third and final feed station to take on water and other nutrition. With 80 km to go, we now worked even more effectively as a group, with constant rotation, no one sitting out for too long. We stayed together, very similar in ability both climbing and descending. The kilometres ticked passed and it seemed like no time before we crossed the finish line. I finished this stage in 15th overall and averaged 31.2 km/h and, because of the way we had ridden so well together, and the stunning coastline scenery, this was my favourite stage of the 3 days. Stage 3 - 171 km - 2,800 m The final stage had been billed as the toughest and, in this respect, it was not to disappoint. With 350 km of hard riding already in the legs and with the prospect of the toughest climbs to come, this was never going to be easy. The weather was great, however, and the sun cream was on. The pace was reasonably sedate at the start and I, perhaps foolishly, contributed too many turns at the front of the peloton. I paid the price as the hills of Exmoor took their toll. I was dropped on Quantock Hill, a 7% gradient for 2.5 km and I found myself riding solo, considerably dropping my average speed. We thankfully descended Crowcombe Hill but then Elworthy Hill, at 2 km and 10% average, took more strength from tiring legs. Sweat was pouring from every pore as I descended the viciously steep Porlock Hill with brakes fully on at times. I needed water and I as I entered the feed station, the main peloton was leaving. I was, however, content to suffer the biggest climb, Dunkery Beacon alone. After I got through the first steep section, a group of knowledgeable bystanders informed me I was only 40% up. My legs were weary as a rider passed me, who also heard that even more pain still lay ahead and he complained vehemently under his breath. We ground up several more steep sections of unrelenting 17% gradient and it was some relief to crest this monster of a climb (by far the most difficult section of road in the whole event) and start the long, more gradual descent. The route cut back on itself and I saw several riders coming the other way. I felt some sympathy that they had some brutal climbs still to come. I seemed to be alone for a long time but was then caught by a fast moving train from Norwood, south London. I jumped on this group, thankful for the company. Cothlestone Hill may only have been 1.2 km but at 10% this late into the event it hurt. Once crested we knew it was mainly downhill and flat and the boys from Norwood put the hammer down. I tried to do my bit at the front but realised I was on my limit and got to the back of a group of around 9 riders and hung on for all my worth. We finished the last 20 mile section in an average of 34.2 km/h and this helped me to finish 25th overall for stage 3. I was more than thankful for their selfless efforts. The Tour of Wessex is an amazing event, which was extremely well organised and took in some wonderful riding. It is definitely very tough and saves it's hardest day for when you are most tired - but in many respects, the scenery on this last day is the most sublime. I camped for the three nights and the Organisers provided the best portable toilets and shower facilities I have ever known for this type of event. There were even flowers in the loos - real ones! If you are looking to participate in a road stage sportive, this would be an event I would strongly recommend signing up for.

1 Comment

Beauty and Pain served in equal measure with brilliant sunshine in the Yorkshire Dales The Tour De Yorkshire was born from the success of the Grand Depart of the Tour De France in 2014. In its inaugural year in 2015, an estimated 2.6 million people lined the route of the professional race. The Sportive offers the chance for amateurs to ride much of the final stage as the pros before they do, including the last 50 km, final 2 climbs, the intermediate sprint and the pro finish line. Distances range from 49 km, 84 km and 129 km and combine the Tour De France delivery with Yorkshire hospitality, amazing crowds and the stunning beauty (and cycling pain) of the Yorkshire Dales. The event copies the format of the Tour De France's 'Etape du Tour' by varying the route every year. In 2015, the route left Leeds, in 2016 it was Scarborough, in 2017 Sheffield and in 2018 it returned to Leeds. Belgium, Greg van Avermaet was crowned the overall winner of the 4 day stage race after a thrilling sprint finish on the final day, which was memorable for a heroic solo attack from Frenchman, Stephane Rossetto, who held on for the stage 4 win after attacking with 120 km of the brutally tough route still to go. Rossetto later said, "I did it in a race that is growing in stature all the time, has more history now, and an amazing crowd. It's been like riding the Tour de France over the last four days. Before the above scenario was to play out, it would be the turn of the amateur fraternity to take on a 129 km route which contained five category 4 and two category 3 climbs and over 2000 metres of climbing. Shortly after 6.30 am, the Maserati riders, who were part of the event's headline sponsors, were released from the starting pen and then, my group, representing the first wave of a total of 5,000 riders. The pace was fast from the start and it wasn't long before we had caught most of the riders ahead. A group of about 10 riders formed and we were working well together, perpetually rolling over at the front and sharing the workload. After 30 km we had passed Harrogate and the first two, longer climbs of Rigton Hill and Hartwith Bank had reduced this group to just 4 riders. Following the next kilometres of undulations and fast descents, the group swelled to around 10 riders, many who were now just hanging on. Most were, not surprisingly, keen to stop at the second feed station at Pateley Bridge, and now there were three of us climbing the Cote de Greenhow Hill, the first of the Pro Course climbs. As one of author, Simon Warren's, 100 Greatest Climbs, Greenhow is no easy ascent. Four sections of climbing of up to 18% deliver the rider to the top of the moor. At this point, I looked round to spy my colleagues but they had been dropped and so I was alone. I rode on for the next 30 km, passing more and more tiring riders, I presume from the Maserati first wave. Now, over 100 km in, a small group of riders hit the climb of Otley Chevin. Crowds were now making their way up to the top of the hill and offered their support or, perhaps, commiserations. At 1.4 km in length and an average gradient of 10.3%, this is another tough climb but I was rolling well and, once again, I was alone up front during the ascent. But suddenly, as I was about to crest the climb, a rider I recognised from the group I had been in before Pateley Bridge came flying past me. It was Bryan Steel, dressed in the colours of his coaching organisation, a former British Olympian and track team pursuitor from four successive Olympic games. I immediately jumped on his wheel and we powered through the rest of the course, including an evil intermediate sprint zone, located on Black Hill Road at an average gradient of 7.2%. As we entered the finish section, a swelling crowd started to bang voraciously on the barriers and I could not resist sprinting against a younger rider across the finish line. Although I grew up in Leeds, I was not yet a serious cyclist and I was unaware of the beauty that surrounds the city. Yorkshire is truly 'God's own country' and it was in fine fettle, serving up the hottest May Bank Holiday on record, the heat of the day avoided after clocking up a satisfying 4:30:35 and an average speed of 27.9 km/h. If anyone is searching for an event in the UK which is both tough and stunningly beautiful at the same time and allows you to soak in the atmosphere of a professional race then look no further than the next edition of the Tour De Yorkshire.

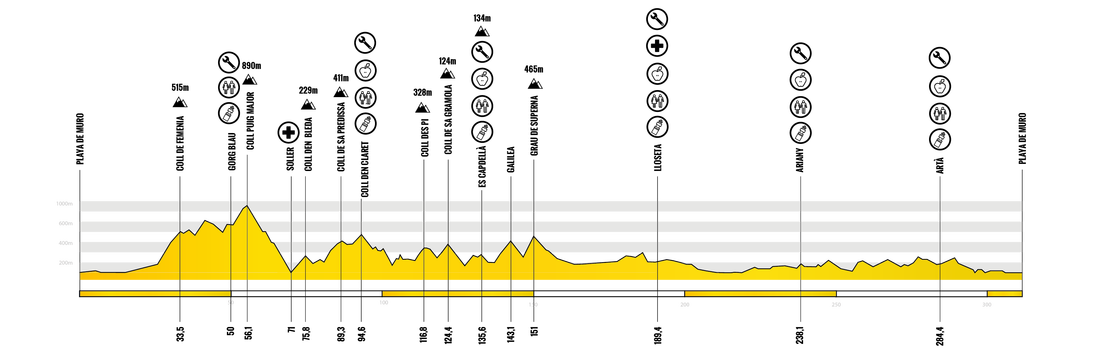

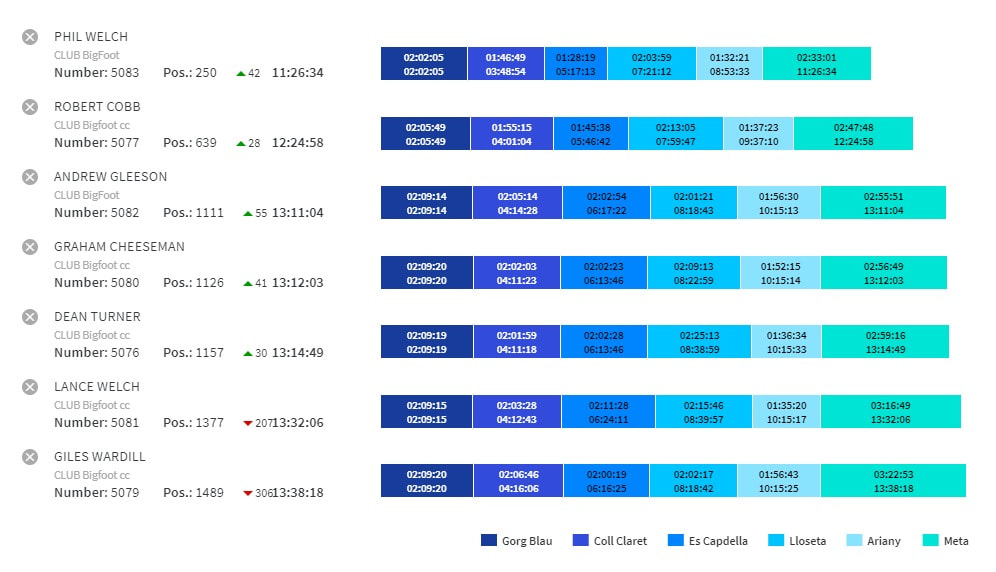

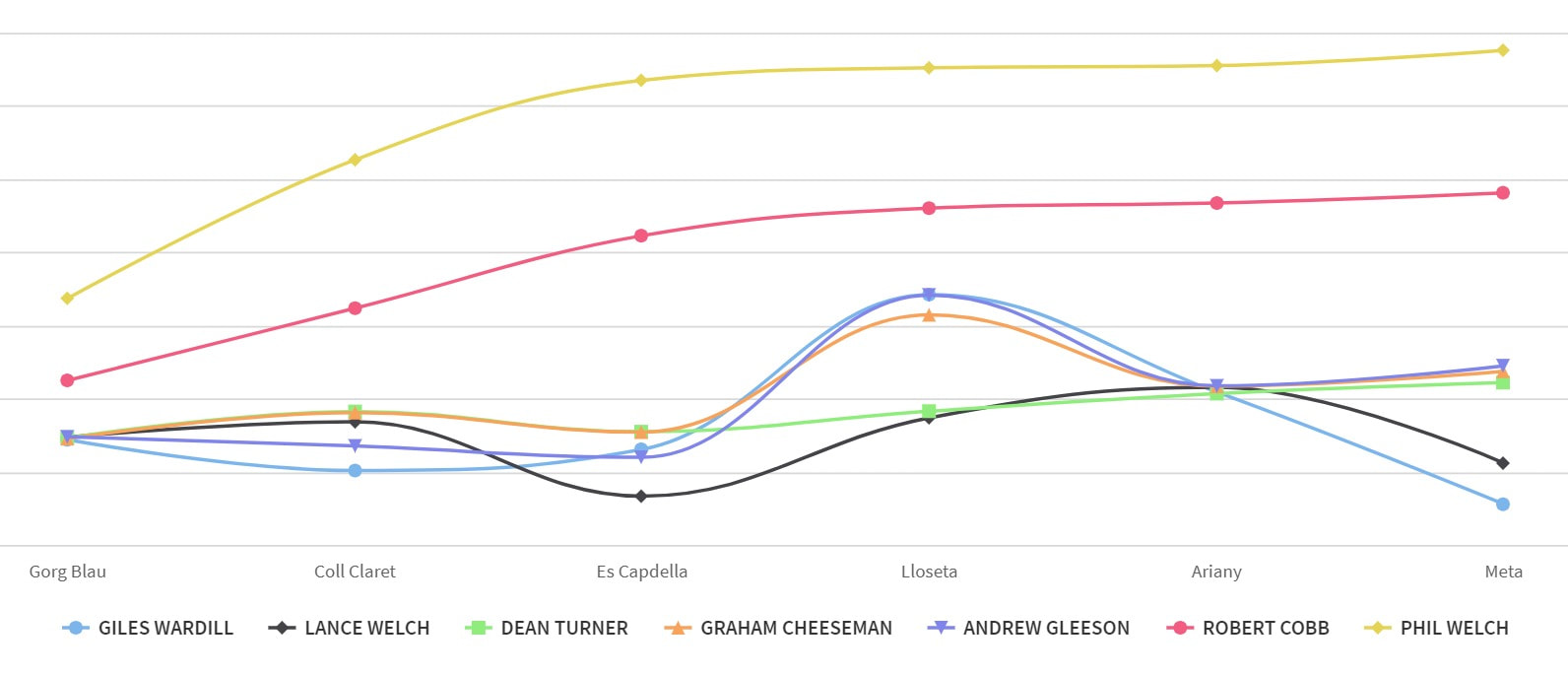

Stunning Sportive in Spain's Cycling Paradise Eight thousand riders, 312 km and approaching 5000 metres of climbing, the Mallorca 312 is truly an epic sportive. Originally conceived as a lap around the island, closed roads have made this original route impossible but the organisers have retained the heart and soul of the original event- the stunning Serra de Tramuntana mountains, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The ninth edition attracted riders from 52 countries, 36% from the UK, outnumbering the Spanish (35%) and Germans (11%), while over 20 media operators covered the event in more than 10 languages. According to the University of the Balearic Islands the Mallorca 312 sportive will have an economic impact of over 16 million euros. Nine riders from the Bigfoot Cycle Club in South East London arrived to take on the Mallorca Gran Fondo. As the first real event of the season, this had been the motivation for our training through the long, cold English winter, with various intrusions by the 'beast from the east' weather system. As a group, we were reasonably well prepared with some longer 200 km group rides and a large chunk of turbo training. With warm up rides taking in Mallorca's finest routes of Sa Calobra and the Formentor Lighthouse, our comfortable base in a spacious nine man villa in Pollensa and the island's exquisite gastronomy being supplemented by our party's own exclusive chef, Lance, all seemed to be going well - but there were concerns from some with mysterious injuries and ailments which had sprung forth and the approach to the event was understandably cautious. We arrived to find ourselves at the back of the starting gate, with thousands of slower riders to battle through in the opening kilometres. It actually took nine minutes for us to cross the start line but then it was a case of weaving through the riders ahead. It wasn't long before we had formed a group consisting of Jay, Robb, Lance and myself and we formed a train of four that hummed with the sound of speeding wheels. After 25 km and averaging high thirty kilometres per hour we hit the mountain climbs and our group quickly splintered. Jay led the way through the hordes of riders and after 55 km we crested the highest mountain in Mallorca, the Puig Major. The descent is exhilarating, plunging over 800 metres into the picturesque port of Soller. With the roads closed, it was possible to use the full width of the smooth tarmac to pick the best lines through the corners for what was a 15 minute white-knuckle ride. We were soon climbing again through the historic township of Deia and on to the first food stop at Coll den Claret (93 km). An array of refreshments were available, but I was in no mood for a picnic, so I swiftly refilled my water bottles and continued on the next long descent. I was refuelling solely on energy gels and ensuring I had one every 30 minutes - I noticed no else feeding around me and knew that they would pay the price later in the day. Towering mountains closed in to our left, as the view to the right opened out to sumptuous vistas across the Mediterranean Sea. These were roads I had ridden on a previous visit to Mallorca and are amongst the most stunning I've ever ridden. Coupled with the almost endless descending this was the most enjoyable part of the ride. Just before Andratx we turned east to face the final major climbs heading towards Galilea and Puigpunyent, before negotiating the numerous switchbacks through a canopy of trees to the Coll des Grau de Superna. The descent was steep and coiled viciously back upon itself and, at one point, my rear wheel skidded from under me but I somehow kept the bike upright. We hit the valley floor and the speed increased noticeably as groups formed to take advantage of riding in a peloton. At the third feed stop, I was greeted by Jay, who was so shocked to see me arrive before him that he asked whether I was doing the shorter 225 km version. This statement was to prove extremely ironic considering what followed. We left together and Jay powered through the wind while I sat in behind. We were joined by a third rider who subsequently refused to work a turn at the front. Jay was furious and rode away at a pace too fast for me to follow. For the next 30 km, I had this rider glued to my wheel, and when others joined, he remained at the back, happy to suck energy from others. Meanwhile, Jay had forged ahead and somehow managed to miss the turn off for the 312. Instead he followed the 225 route and by the time he realised it was not possible and deemed too dangerous by the organisers to turn back and re-join. He finished his event by adding the Formentor Lighthouse Loop and clocking 312 km in his own unique way! Mallorca has matured into a veritable utopia for cyclists with its terrain, climate, culture, exquisite gastronomy (it now has 6 Michelin-starred restaurants) and snooker table smooth roads. Money was pumped in to resurfacing the roads around the mountains months before the 312. However, the loop south east towards Manacor was less spectacular and the pot-holed roads more a memory of our training rides in Kent. Having started well behind the quickest riders, there was now no fast groups coming through and as I continued to catch tiring riders, no one was able to work with me and so my speed suffered as a result. After 285 km I re-filled a final bottle at Arta, a town renowned for its pavement cafes and quaint shops. There was a party going on, beer was flowing and it was almost as if the finish line had been transported 25 km south. I briefly soaked in the carnival atmosphere, before continuing to the finish. Our small group of four doubled in size and the pace quickened over the final 15 km as we hurtled into Can Picafort and towards the finish line at Playa de Muro. I crossed the line in an official time of 11.26 (11.10 moving time) in 250th position. Robb followed next, then Andrew, Graham, Dean, Lance and Ed, with Jay and Andy completing the shorter distance events (although Jay insists his version of the 312 should form the blueprint for Mallorca 2019)!

A Slice of Honeymoon Heaven Proves Just the Tonic Santorini, stunningly beautiful, volcanic rock heaved from the bowels of centre earth, its inhabitants settling precariously on its cliffs, which form the rim of a massive dormant volcano - a beast responsible, in 1500 BC, for the second biggest eruption known to man; considerably bigger than Krakatoa's, and the ensuing massive, deadly Tsunami was the precursor to the eventual destruction of Europe's ancient Minoan civilisation on Crete, 110 kilometres to the south. Oblivious to its devastating legacy, my wife, booked a two week Christmas break in Fira, the capital of Santorini. But on finding out that travelling to the island would involve at least three flights via central Europe and Athens, Greer promptly decided to cancel. However, this would mean losing all the money, so our fate was sealed - we were going to Santorini. Perhaps we would have quite happily let the money go if we had known how treacherous the flight from Athens to the island was going to be. As we approached the short landing strip, the pilot was fighting to keep the plane steady. The sky was intensely dark, then set alight, as lightning continuously forked wildly from within the heart of the storm clouds. We had been circling the island, waiting for clearance to land for some time, the other passengers shifting awkwardly under seatbelts pulled far tighter than is usual. The captain eventually announced we would have to return to Athens to retrieve a bigger plane. However, back in Athens, we were then instructed to board the 'same' plane and fly back into the eye of the storm. For once, everyone paid close attention to the safety briefing. The pilot had been changed and he sounded much older, so I guessed he was far more experienced; this time we flew safely into Santorini airport. Rain and gale-force winds greeted our arrival on terra firma, but the feel of solid ground, be it on top of a sleeping volcano, was a welcome comfort. Our expectations for the two weeks were not particularly high, a feeling further reinforced when we arrived at the hotel. The Minoans are known for being an advanced civilisation but the modern bunch have yet to develop a fully flushable toilet capable of handling toilet paper! Over the following fourteen days, Santorini's attraction began to break forth from its core and we were buried under a blanket of beauty, to be forever etched in our memories. The following day the winds were still strong so initially we explored close to the hotel and the town of Fira. The white-washed houses, hotels and restaurants clung to the cliff edge; from a distance they looked like snow-capped mountains. Charming art and craft stores adorned the narrow streets and a cable car plunged down towards the old port below. The following day, the wind had relented, while the sun burnt through the clouds raising the winter temperatures to 17 degrees. A longer walk to the village of Pyrgos, revealed a viewpoint stretching across much of the island; and quaint narrow streets where local, stray cats roamed, appearing surprisingly healthy. Christmas Day was one we will never forget. The plan was to hike from Fira to Oia, the islands most northerly point. Greer and I have walked all over the world, but nowhere as stunningly beautiful as this. The trail meanders along the cliff edge, steeply rising and falling, each twist and turn revealing fresh wonders. To our left, the deep blue water glistened as it caressed the small central islands of Nea Kameni and the older Palea Kameni; the centre of Santorini's volcano. As we progressed along the walk, the houses became larger, infinity pools apparently an obligatory element in their grandeur. The trail then became more rugged, revealing a more natural beauty. After negotiating some particularly steep and rocky track, we entered the remarkably picturesque town of Oia. Chinese couples wander along the narrow streets, waiting for the sun to set and romance to blossom. The popular Chinese movie 'Beijing Love Story' was filmed on the island, sparking an explosion of volcanic proportions in tourist numbers. We return to Fira and pass the outcrop of Skaros, where, in 1421, an inviolable castle once stood before almost completely collapsing into the deep waters below after several devastating earthquakes. (A few days later we trekked to a church, precariously perched on its precipitous slopes, Greer only managing to complete the trip after we had happened upon an old lady, probably in her early 90's, returning from the church carrying several bags, a trip her daughter told us she did on a weekly basis). Soon after, we reach the high cliffs of Firostefani and are fortunate enough to witness the sunset completely alone. This clearly does not disappoint - the sky above Nea Kameni turning yellow, orange then blood red - a perfect night cap to the most wonderful of days. It was always going to be difficult to match that special day, but our trip to the volcanic centre came very close. We descended the 588 steps that led to the old port, passing the donkeys that are still used to take tourists to the cliff's base. An old wooden boat took our party to the volcano centre on Nea Kameni and then a steep walk culminated in witnessing various sections of rock smouldering, as if the dormant volcano was reminding us of its presence. Back on the boat, we docked at Palea Kameni and two hardy American couples dived into the deep, cool waters prompting me to quickly follow - so five of us swam across to the muddy, hot (well, actually lukewarm) springs. The water bubbled around us before we finally mustered the strength to swim through the cold waters that lay between the springs and the warmth of our boat. Equally as fun, was our day spent exploring the parts of the island, too distant for our daily walks. For this we hired an ATV or 'All Terrain Vehicle' - basically a small buggy with a 200 cc engine. First stop was the 'Monastery Profitis Elias' perched on top of the islands only mountain. The views were stunning and gave a great impression of the islands overall size and scale. Next, we ascended the cliffs south of Kamari, visiting the remains of the ancient town of Thira belonging to Dorian colonists from Sparta. This gave us a great impression of how this advanced race of people had lived in the early 8th century BC. Later, we visited the ancient remains of the prehistoric city of Akrotiri. Life here came to an abrupt halt in the 17th century BC, when the Minoans abandoned the city following powerful earthquakes and the enormous volcanic eruption that followed. Like Pompeii, the volcanic material that covered the island preserved the sophisticated settlement, which nowadays testifies to the Minoans extremely high level of development. Visits to nearby Red Beach and then to Perissa's Black Beach, the Santo Winery and Oia again for the sunset, capped a wonderful day of exploring - mention must be made to the fun I had driving the ATV - for a small vehicle, it had ample power and speed, although Greer (who was my passenger) may not agree as she made constant reference to reducing our speed! Greek hospitality on the island is exceptional and it is clear they value the tourists who contribute a great deal to the Santorini economy. There were plenty of food and drink choices, while sampling the local fare such as moussaka, souvlaki, fava, yoghurt and the local wines was always rewarding. We were frequently offered extra food and drink at no extra cost and were warmly treated by the locals. This hospitality extended to the local dogs, which appear to wander the island freely. On two separate occasions, while exploring the island around Monolithos, we were accompanied by one of these dogs for several kilometres before they eventually return, we assume, from where they came from. Several days later, and again on separate occasions, both these dogs came bounding up to us, tails wagging, a bounce in their step, clearly recognising us from before. It is this feeling of belonging that is similarly felt between the visitor and the island - one that will surely remain for a very long time to come.

When 24 hours of riding just isn't long enough Ultra events, when you're deep into them, are just miserable, and the people who succeed are those who can cope with that misery - Greg Whyte OBE (former Olympic Pentathlete & Sports Scientist) The inaugural Red Bull Timelaps 25 hour race took place in the shadow of Windsor Castle, on the weekend of the UK being plunged into another long winter. Six hundred riders, comprising 150 teams, were readied to do battle in Windsor Great Park, as part of the World's longest one day bike race. Originally posted online by Jamie Baskerville as a joke, the 25 hour race proved too enticing for Robb Cobb and myself and we soon entered a mixed team with Cassie Baldi making up the fourth member of our Bigfoot outfit. Scheduled to coincide with the clocks going back, the expectation was for cold, grim weather conditions but on the morning of the race the weather was mild, no rain was scheduled and the night temperature was predicted to be 10 degrees. Surely 25 hours in these conditions would be an absolute joy! Our illustrious team leader took to the start line but, due to our late entry, Jamie found himself at the back of the grid with virtually the whole field ahead of him. Jamie took to the task of picking his way through the field like a seasoned veteran and by the second lap he was part of the lead group. Then disaster struck for one rider, who overcooked a descent, found he had nowhere to go and subsequently plunged into a group of slower riders, leaving one being rushed to hospital with multiple broken bones. The race was halted and after a long stoppage, Jay was, once again, placed at the back of the starting grid. Nevertheless, he was soon back in the lead group after scrambling a second time through the mass of riders ahead and posting a time of 9.30 on his 4th lap, an average speed of over 42 km/h. Strategy was going to be a key component in this race and we had decided on completing four 6.6 km laps before pitting and sending out the next rider. Robb took the armband and put in his fastest lap of 10.42. By the time I took the team armband, the field had broken up and it was much harder to find an appropriate group to work with. I solo time-trialled for much of the undulating course, but still I appreciated the well-surfaced and traffic free roads. Cassie took her four lap shift, our position around 29th overall and 7th in the mixed. By the time Robb finished his second stint, the park had been plunged into darkness. Team spirits in our transition area were still high. We were confident that we would gradually move up the field as other teams tired, making the most of the endurance qualities we all possess. Indeed, I have done nine solo 24 hour and several 24 hour team events in the past, albeit on a mountain bike. As for Jamie - well he's just strong and only fatigue from the high mileage he'd been doing in the last couple of weeks could possibly slow him down. We approached the 2am point and the start of the Tag Heuer Power Hour. We were gradually moving up in the overall classification and only four minutes separated 4th through 8th in the mixed. We timed our changeover to Jamie (who would undertake the whole Power hour alone) to maximise his time on the special 4.4 km loop. Jamie stayed with a select front group and put in an incredible 8 laps, which would count double for the team. Unfortunately, most of our mixed rivals had managed to do the same and we were still 7th. The clocks had now gone back providing the race with that extra hour. The most important aspect of racing 24 hours is pacing and nutrition. Pacing is handled mentally by breaking the race down into manageable time chunks and setting realistic short-term goals, such as completing each lap in a set time, while nutrition is keeping hydrated and topped up with carbohydrates and electrolytes. We would crave chocolate one minute then savoury biscuits the next. Stomachs started to react adversely - Cassie was feeling sick and Rob wanted to vomit - not surprisingly, when we found out he had drunk six cans of Red Bull and was hydrating with carbonated water! Both needed to take a brief break to lie down and sleep off their ailments. Both came back strongly. This was undoubtedly aided by the emergence of daylight. During my 6th stint, just after six o'clock, the sun appeared briefly, but was rudely pushed aside as heavy clouds brought the first precipitation of this event. Fortunately, this proved a brief interlude, the sun reappeared and the road began to dry out. It was now quarter to ten, 22 hours 45 minutes into the event, and I went out for what I believed would be my last four laps. I managed to jump onto the back of a fast-moving group of riders and I felt like I was truly burying myself for the team. I was lapping considerably faster than previously, so much so that my fourth lap was only five seconds slower than my fastest lap from the day before. As I approached the finish line, both adductors began to cramp badly but I knew this was to be my final lap and consequently, I ignored the pain to finish strongly, and triumphantly passed the armband to Jamie. My joy at finishing so fast was immediately ripped from beneath me when Robb and Cassie announced that I would need to go out again in forty minutes time. In no uncertain terms, I told them they had to be kidding. But on reflection, I was holding down decent lap times and it was necessary to get three laps in before the cut off time of 25 hours. It was going to take another almighty effort. Ten minutes later, I was back on the rollers, going through my customary warm-up, mentally preparing myself for another 'one-last effort'. I was telling myself that all the time spent in the cold, the rain, the wind and on the Wattbike or rollers is for these moments to prove that it is all worth it. Jamie came in and I was thrust back onto the circuit straight into the path of one of our mixed team rivals - this would be a battle to hold on to 6th place. My rival was a muscular female Time Trialist and there were three laps to race, if we were to both make the time cut. She would power away from me on the flats and I had to focus to stay on her wheel. The short climbs would give me an edge but she would work hard to close the gap at the top of each climb. The cramping had not re-emerged and we were mutually benefitting from each others slip-stream. The climb before the last lap began, provided another opportunity for me to break her resilience. I crested the hill and anticipated her re-joining me as the road flattened out again - she never did - I started the last lap alone - It was now a race against the clock. Could I make the cut off time so the current lap would count. I crossed the line with seconds to spare but I was broken. A look up to the scoreboard confirmed our 6th position and 21st overall, a result we were all more than satisfied with. We had dug deep within ourselves, all fighting our own personal battles and all emerging with satisfaction. The longest one day bike race in the world had been successfully vanquished. Team Statistics: Team Bigfoot: Overall: 21/134 ; Category: 6/42 Jamie Baskerville: Number of Laps: 24 (plus 8 Power Laps) ; Fastest Lap: 9.30 ; Average: 11.32 Phil Welch: Number of Laps: 31 ; Fastest Lap: 11.15 ; Average: 12.19 Robb Cobb: Number of Laps: 28 ; Fastest Lap: 10.42 ; Average: 12.31 Cassie Baldi: Number of Laps: 21 ; Fastest Lap: 11.52 ; Average: 12.40

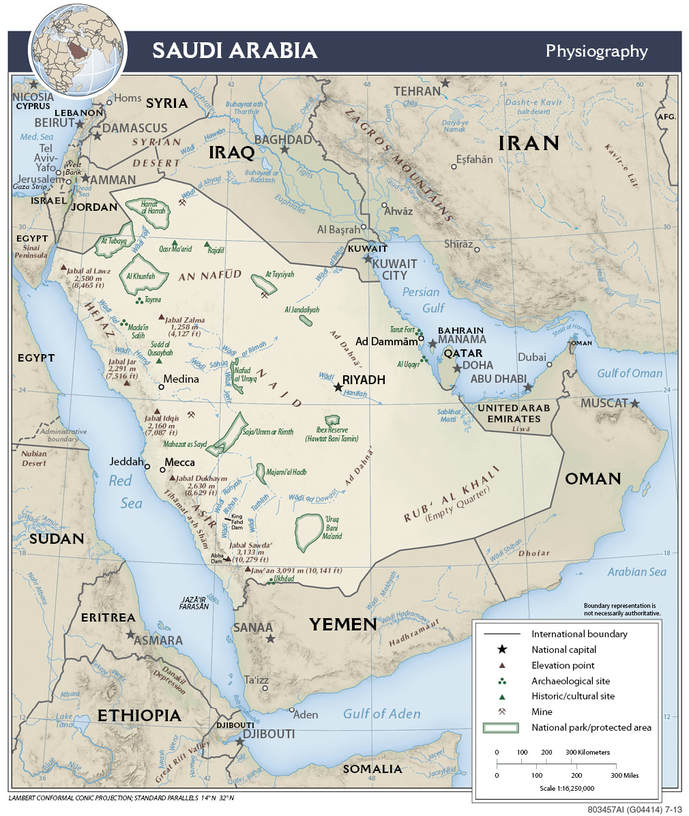

Ramo Pro Cycling Training Camp Contributing to a Cycling Revolution in Saudi ArabiaMission Statement To lead the current and younger generation into the future by helping to create significant changes in infrastructure and awareness in cycling in Saudi Arabia and beyond. It is hoped that the Ramo Pro Cycling Training Camp can help to inspire Saudi's in the field of cycling, by introducing new experiences and expanding knowledge, leaving its fingerprint wherever the training camp goes. Like a pebble dropped into a lake, it is hoped the cycling message will spread from its source to other areas in Saudi and beyond. The Company In August 2013, ex professional Syrian Sprinter, Omar Hamad, created Ramo Pro Cycling in his hometown of Famagusta in Cyprus, with his business dealing in cycle rental and tours. Omar later developed a wish to bring cycling to schools and inspire future generations of cyclists and his desire to coach and educate has now been brought to faraway Saudi Arabia. The Team An international team of specialists was brought to Saudi Arabia. The team consisted of Omar Hamad (Director / Event Organiser / Head Coach); Ameer Alrimawi (Logistics Coordinator / Public Speaker / Team Motivator); Phil Welch and James Novak (Cycle Coaches); Constantinos Demosthenous (Head Mechanic) and Dr Rayan Karkadan (Health and Fitness Coach). Standard of Equipment With the exception of a couple of specially imported road bikes (Merida and Specialised) the majority of bikes were Trek or Performer and were mainly heavy hybrid and mountain bikes. On our first day, we were confronted with bikes with baskets, bells and horns and the majority had flat pedals, the riders flat shoes. Level of Knowledge Several of the riders told us they were 'pros' but it appears that the use of this word merely meant that the cyclists here rode regularly and had more advanced equipment than their peers - not that they were being paid to cycle! Cycle Coaching Coaching took place on the first five days and concentrated on improving bike handling, core cycling and group riding techniques by improving bike handling skills, balance and coordination, developing rider awareness of others around them, signalling and the ability to select the appropriate gearing and cadence for the chosen terrain. The riders were divided into three groups (beginner, intermediate and advanced), each group coached by a member of the Ramo team. While riding on public roads the cyclists would be led and protected by the local police and ambulance service, support cars, a mobile mechanic and recorded by a professional film crew. Cycle Touring Two days were devoted to Cycle Touring, where the group would ride together as a peloton, again supported and protected by a team of vehicles. Local areas and places of interest were visited, providing the opportunity for the group to socialise, drink tea and eat local specialities, sing, dance and generally enjoy the beauty of the mountain surroundings. Strength and Conditioning Five evenings a week, the riders would be engaged in exercises to develop their strength and conditioning for cycling. Nowadays,it is well known that cyclists need to work on their strength, particularly their core and lower body, but also their upper body strength. Cycling is a non-weight bearing activity and strength training will help build bone density while building stability and power. Stretching, understanding and experiencing how to use foam rollers and trigger- release balls for myo-facia release will help protect the riders from injury, reduce pain and increase flexibility. Cycle Education Evening seminars were given in the History of Cycling, Cycle Safety, Mechanics and Nutrition to help educate the riders in these four crucial areas. The Future Ramo Pro Cycling hopes to help increase knowledge and awareness in cycling in the Al-Bahah region and for this to spread across the country and beyond. Ramo represents an important link in the chain, driving the wheels of change and bringing knowledge and awareness to future cycling generations.

Rugged, Rocky Mountains, a Cornucopia of Delicious Food, Vicious Wild Dogs, Suicidal Drivers, Genial Locals and an Omnipotent King Eight Lessons to be learnt from my first Eight Days in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Lesson 1: Visas are almost impossible to obtain...unless you know the King I was now given the task of obtaining a work visa, which proved to be a major obstacle to my trip. Initially advised to go through an agent, I was asked for a substantial amount of money and an array of documentation that would take weeks to collect. The agent would provide extra assistance but for an ever-increasing amount of money. Desperate, I decided to go directly to the Embassy. This was once again met with numerous obstacles but once the Embassy knew the Prince of the region was sponsoring our cycling event, the mood changed, people mobilised and a visa almost instantaneously appeared in my passport. Miraculously, I was going to Saudi Arabia. Lesson 2: Saudi Arabia is not just a burning hot desert Initially, I was astounded that a training camp would take place in the desert in the middle of summer with temperatures of around 50 degrees. How on earth would that work? However, the city of Al Bahah is nestled in the southern part of the western coastal escarpment and consists of rugged high mountains at an altitude of over 2100 metres with accompanying cooler temperatures and precipitation blown from across the Red Sea. Temperatures range between 18 and 30 degrees, with some rainfall, conditions more than conducive to pleasant and comfortable cycling. Lesson 3: Drivers in Saudi are maniacs An unmistakeable truth is that every driver here appears to have taken a cocktail inducing insanity and impatience in equal measure. Crossing the main street in Al Bahah becomes a mission in speed, agility and reflexes - reaching the other side unscathed a minor victory each time the task is undertaken. Car horns remind me of a symphony of cicadas, only these are man-made sounds that do not calm the senses. Being driven in a car, no matter who the driver, offered no further comfort to personal safety. Two lanes are filled by three cars abreast, signalling is non-existent and speed limits ignored. On our first day, we witnessed two collisions, the occupants of the cars gesticulated and just drove on blasé to the damage to their vehicles. It appears that traffic rules are merely suggestions. I was even told that Saudi drivers don't use their indicators because they believe that they shouldn't let their enemy know their next move. Lesson 4: Saudi Air is Polluted According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Riyadh is one of the most polluted cities in the world, although not as bad as Khuzestan in Iran or Ulan Bator in Mongolia. Apart from heavy traffic, the occurrence of sandstorms and pollutants from industrial waste contribute to the poor air quality in Riyadh. Fortunately, Al Bahah is over 900 kilometres away, is high up in the mountains and doesn't suffer as much from pollution. However, one of the most noticeable aspects of being outside in Al Bahah was the smell of car fumes. Not surprising, when so many drivers choose to drive large four wheel drives and the cost of petrol is over five times less than the UK. Breathing in the dry air also resulted in inhaling small airborne sand particles although the rain that fell in our first week helped to clear the atmosphere. Unfortunately, several of the historical sites and beauty spots we visited were covered in discarded litter although this issue is apparently being addressed. Lesson 5: Saudi life is structured and religious The official religion of Saudi Arabia is Islam and the people pray five times per day. To allow workers to pray, shops and restaurants will close for around 20 minutes. Incidentally, Al Bahah is a mere 300 km south of the Holy City of Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammad, the site of Muhammad's first revelation of the Quran and the direction of Muslim Prayer. Lesson 6: Saudi People are friendly and respectful Saudi citizens invariably welcome visitors with a smile a warm handshake and sometimes even a hug. They are keen to practise their English and equally to teach their own language to anyone willing to stumble their way through their lexis. They are a respectful and hospitable people who are undeniably proud of their families and genuine in their offer to accommodate your stay. Lesson 7: Saudi Food is delicious One of the wonders of travelling is sampling the regional and national food and drink. Saudi food frequently consists of rice, lamb, chicken, yoghurt, potatoes, breads, fava beans and dates. Saudi is the highest consumer of broiler chicken in the world and this might explain why our initial hotel served our party of five chicken and rice three successive days despite us all ordering a variety of different dishes from a seemingly extensive menu. Lesson 8: Animals are not cute and cuddly On our first day we managed to see a harem of Hamadryas Baboons, which are found in large numbers in these mountainous regions, crossing the road ahead of us - if you threaten their territory they may be driven to defend themselves or if you have food (we were carrying bananas), they may try to attack. We already knew that baboons could be exceedingly dangerous and we waited for the troop to leave the road therefore allowing us to pass safely. On my third day in Al Baha, I was riding in the mountains when a pack of wild dogs cut off the road, led by the alpha male, a snarling, slobbering mass of white fur. I was at the top of a climb, breathing heavily and in no state to remain calm - I beat a hasty retreat down the mountain, returned a few minutes later to the same spot but the dog didn't relent in its aggression, sending me scurrying for a second and final time. Concluding Thoughts Saudi Arabia is, in no way, the country I expected it to be, at least from my brief experience in Al Bahah. I'm sure this is partly due to the image portrayed in the media and the fact that it is not completely open to non-Islamic tourism. This image seemed to be confirmed by the difficulty I had obtaining a visa but, once in Saudi, this image soon melted from my mind. Al Baha has wonderful mountains, green areas and an agreeable summer climate. Its people are structured and religious but they are also warm, relaxed and extremely friendly. Caution does however need to be heeded on the roads and when confronted by wild animals. But humans always have the last laugh - shortly after arriving in Saudi, I witnessed in full public view, a live sheep being thrown unceremoniously into the boot of a Mercedes car as my local driver sped manically along the main street - perhaps this is the reason why Saudi food is so fresh and delicious.

Nothing Short of Sensational

Touted as the hardest one day road Sportive in Europe, the Alpes Marmotte certainly has a fearsome reputation among the amateur cycling fraternity. With over 7,500 entrants, the Granfondo takes in four legendary mountains which regularly feature in the Tour De France, the Glandon, Télégraphe, Galibier and Alpe d'Huez, and covers 174 km with around 5,000 metres of climbing. Stories abound of participants bursting into tears of joy and relief at the finish, while others talk of the carnage of broken riders at the side of the road during the final climb of Alpe D'Huez.

The weather in the high mountains is unpredictable and the days leading up to the 35th edition of the Marmotte were not encouraging, with cool temperatures and rain forecast. Arriving in Geneva, three days before the start, merely seemed to confirm the predictions with storms unleashing heavy precipitation on the Swiss city. With one day before the event, the weather took a positive turn and the black clouds were pushed aside by less threatening skies. But still atop the 2645 m climb of the Galibier the temperature was -2 degrees and snow had fallen.

To begin the event, it was necessary to descend from our base in Alpe D’Huez to the start at Bourg D’Oisans. Extra layers of clothing were shed at the start but despite the coolness hanging in the air it was dry and, incredibly, no rain was predicted. Despite the organisers sending the second start wave round the town and early confusion and frustration ensuing, we were eventually on our way, immediately forming trains of equally paced riders and tapping out a fairly quick tempo to the foot of the first climb, the Glandon.

It is sensible to heed the advice of others and not to let the adrenaline, built in the early fast kilometres, to flow uncontrollably to the head. The overall gradient of the Glandon is relatively steady, averaging 5%, but the climb has some downward pitches which lower the average and is extremely long, continuing for 28 km. It was here that the field began to spread out, making it necessary to move past others on the left, a pattern to be repeated throughout the race. Even quicker riders seemed to pass effortlessly on my left, which seemed to confirm the high standard of competitor in this event. The road dropped steeply for short sections, which tended to break the early rhythm rather than offer relief, before pointing up once again to the clouds and mist above. On a drive the previous day, I had seen a succession of spectacular waterfalls but now these could only be heard momentarily as they were passed in the gloom. Nearing the top, the mist had wrapped itself all over the peak, only to unveil a rather chaotic feed station. Despite this section being time-neutralised, due to the danger posed by the descent's steeepness, I lingered a little too long. I was sweating from the climb and the chill in the air immediately dropped my body temperature.

I began the descent with an additional windproof gilet but I was cold and longed for the warmth of the valley. I decided to descend with care, knowing I wouldn’t lose any time. Just as I had stopped the shaking, my lower back began to ache and unfortunately I was unable to enjoy the flowing corners lower down the mountain. I saw a couple of my riding buddies before the timing mat, which would signal the end of the neutralised zone. On dismounting my bike my left quadricep cramped painfully and didn’t release for 30 seconds. Not the best sign so early on into the event – now I would have to manage the cramp for the next 140 km.

We rode through the valley, larger groups formed and the pace increased. I ignored the water stop at the foot of the Telegraph climb, keen not to break my rhythm. The one hour climb up the Telegraphe was exhilarating, with incredible mountain views all around. The gradient averaged 7% but the climbing was constant and the legs were now accustomed to tapping out a steady beat. A brief descent took riders to the beginning of the Col Du Galibier. Again, I ignored the feed station, content in the knowledge that I was feeding and hydrating successfully on the bike, a skill I'd acquired from nine solo 24 hour mountain bike events, and keen to avoid the scrums of hungry and fatigued cyclists.

It was at this point, I began to notice I was travelling far more comfortably than the riders around me and I was moving quickly through the moving mass of cyclists ahead of me. I would sporadically jump out of the saddle to offer relief to my legs as the 18 km began to whittle away. The views were awe-inspiring, particularly the formidable and imposing Meije Mountain peak to the south, the last major alpine summit to be conquered by climbers. The last section of the climb, the steepest, seemed to present itself as a wall of switchbacks ahead. However, I was surprised at the flow that I felt as I made my way up the final section. Making use of a private feed station 1 km from the summit, I grabbed more water and a handful of gels, before cresting the climb. At 2642 m, this is the highest point in the Marmotte, as it has been in previous editions of the Tour De France. I was keen to avoid my mistake on the Glandon, and therefore immediately rolled over the peak and onto the descent.

At around 50 km, this descent is the longest and without doubt the most exhilarating I've ever experienced. It took a while to drop enough altitude to stop the shivering, but on reaching a certain height, it was almost as if the gods had kindly thrown an electric blanket around my torso. The cold was replaced by sore and numb hands and, at times, I had to readjust my grip to confirm I was actually pulling the brake levers. Then I would plunge at spine-tingling speed into the first of several tunnels, more than happy to re-appear on the other side still in one piece. On the lower slopes, we would pass small villages, the gradient would level and offer some relief as I sat more upright and out of the drops, before plunging once again into the valley below.

Finally, I reached the valley floor, and riders regrouped into fast moving pelotons, driving towards the last climb of Alpe d'Huez. To reach the finish in the village at the top of the Alpe d‘Huez it is necessary to navigate the 21 world famous hairpin bends, enduring 14 km of road averaging around 9% gradient. Once again, I ignored the feed station and kept my momentum for the last big climb. The first few bends are the steepest and I wondered how my legs would feel. To my surprise, I was still climbing well and, further to my amazement, I saw my much stronger training partner stretching out cramp at the side of the road. He joined me on the climb, and we chatted as if we were out on a training ride and not finishing a fiendishly difficult bike event. The switchbacks seemed to quickly come and go and then the church on Dutch corner appeared, so-named since Dutchmen won eight of the first 14 finishes in the Tour De France and is where the Dutch now congregate on race day. We stopped briefly at a private water station, primarily to remove clothes added at the top of the Galibier, two hours previously. The temperature was now well into the twenties, quite the change from the freezing temperatures of the Glandon and Galibier.

With 7 switchbacks to go, I continued the final kilometres, my friend hovering just ahead, serving as a guiding light to the top of the col. More and more people appeared on the side of the road offering further encouragement as the finishing line approached. Once through the village, I picked up the tempo, finding energy reserves I had no idea I possessed. With 200 metres to go, I majestically rose from the saddle and began my sprint for glory. Within seconds my gilet fell from my back pocket and wrapped itself around my rear wheel and drive chain bringing me to an unceremonious halt. As I fought to release my gilet, I had a momentary vision of picking my bike up and, emulating Chris Froome's feat on Mont Ventoux in 2016, running with my bike to cross the finish line. These fanciful thoughts were interrupted by one kind spectator who picked up my bike allowing me to finally free my gilet. I remounted to a massive cheer, only for my chain to spin off. A third time, another cheer but I failed to clip in, my foot slipping embarrassingly off the pedal. One final roar, and I appeared to be swept down to the finish, crossing the line in a time of 8:06:59.

Without doubt, the Alpes Marmotte is the most breathtaking ride I've ever experienced on a road bike and I would fervently recommend it to any rider who is looking for a momentous challenge in a spectacular environment. It's incredible to think that the professionals actually race up these mountains, rather than merely survive the day but anyone able to complete this event deserves the utmost respect.

The Fred takes on the Devil in a Winner takes all showdown Tale of the Tape

The first of our challengers for the toughest Sportive in the UK comes from the rugged hills of Cumbria and with the Fred weighing in at 180 km and with nearly 4,000 metres of climbing she's certainly not a lightweight. Supporters of the Fred were prepared to dish out plenty of pre-ride trash talk: boasting several 30% big hitting gradients with many riders ranking it alongside European heavyweights such as the colossus Alpes Marmotte in terms of difficulty. Round 1 vs The Fred Sunday 7th May 2017: I took to this challenge, well aware of the Fred's reputation as a big puncher and it wasn't long before the first big blows started to crash down on me. Kirkstone Pass at 454 m is the highest point on the route and came early, just 23 km in. I had started fast and the first 74 km had made little impression. Honister Pass was to change this. The Fred caught me unawares and the steepness of the climb, combined with the heat of the sun and poor choice of jacket, meant I was sweating profusely. A friend, Chris Bell, passed me at this point and his well-intended push did little to boost my morale. I was on the ropes and close to being given a standing count. I hung on for the crest of the climb and the descent breathed new resolve. I had survived the Fred Whitton's biggest assault so far. Newlands Pass was negotiated comfortably and at Whinlatter Pass, the sight and support of two friends, Jason and Geoff, further restored my inner vigour. The Fred seemed to ease back on the assault, the early knockout no longer an option. Time for it to wait, bide its time and then come out guns ablazing. Hardknott Pass, is the undisputed King of Climbs and arguably the hardest stretch of road in the UK. An act of cruelty on the part of the organisers, this 2nd century Roman road is ascended 158 km into the event when the legs are weakest. The climb starts steeply - two sets of switchbacks through 25% corners, then a levelling off, but looking ahead only reveals the enormity of the task ahead and 30% switchbacks. Through the first, I was once again in trouble and hanging on before the Fred finally sent me to the tarmac. Within 20 metres I was round the bend and back up determined not to be hit by the knockout blow. With renewed vigour, I made it up the final part of the climb and then with enormous pride, I conquered Wrynose Pass and it's 20-25% bends. The Fred had thrown its best shots but, despite a couple of uncomfortable moments, I had survived its brutality and finished the rest of the ride in 7 hours 10 minutes with energy to spare. The Dragon Devil, part of the global L'Etape series, weighs in at a colossus 300 km and a hefty 5,000 metres of climbing making it a worthy rival to the Fred. Hailing from the Brecon Beacons of South Wales, the Devil does offer three softer options of 100, 153 and 223 km but none can be considered easy. Round 2 vs The Devil Sunday 11th June 2017: The Devil, presents a subtely different challenge to the Fred, in that it is more a skilled tactician, which will throw combinations of jabs and bodyshots and wear you down over time without the big blows. Maximum gradients are more in the region of 25% but even these feature far less frequently than they do in the Fred. Despite all the climbing metres, the climbs are more alpine-esque and gradual in nature. After a good luck message from Chris Froome and a comical performance from Didi the Devil and his trident, I was soon experiencing the gentle but long climbs of Bwlch and Rhigos. I was working within a strong group of riders and my average speed was well above 28 km. I'd come out swinging and had landed some of my best shots. But was I in danger of punching myself out. The wind was troublesome, particularly when it caught my deep-sectioned wheels on the descents, taking my bike sharply across the road, but it was still manageable. The Devil's Elbow, 89 km in to the ride, with an average gradient of 9.8% and some sections of 20% was safely negotiated. A glacing blow at best. At 125 km, several Devil riders appeared to have decided they had suffered enough punishment and took the turnoff for the shorter Gran Fondo route. The weather was worsening and rain was inevitable. The hardy (or more appropriately, the foolhardy) remained on the Devil course. My small group was split as we tried to negotiate passing traffic on very narrow roads. Several sections were now being ridden alone. When I finally connected with other riders, we were sent up a ridiculously steep lane that was not on the official route. This was the start of the weakening process. I was now cold and shivering but, pig-headedly, I rode on with my rain jacket still in my back pocket, hoping I would warm up after my stop as we worked out directions to the proper route. But I was weakening and I was still cold. The Devil's Staircase, 190 km in, proved the biggest assault to date. Not quite as steep as the climbs in the Fred but, with gradients over 25% and averaging 12% in 1.3 km, it is similar to Hardknott in that it comes when the body and legs are already tired. But in this case, the storm that hit at the top was the knockout blow. Heavy rain turned to large hailstones. The spray jacket was now on but it was too late. I was shivering once again and, worse still, I was unable to eat and drink. I was out on my feet. The descent was treacherous but did transport me to drier and warmer conditions. I was able to stop and regather myself at a feed station and ate vigorously, whereupon I felt patched up and propelled myself back into the contest. I was much weaker now and in survival mode, starting to count the kilometres as they slowly ticked down. Black Mountain didn't appear too bad considering the punishment I had already taken but now the senses were weak. The climb out of Neath was not the biggest but the power had gone and it proved a bigger challenge than it should have done. At the finish, just over 12 hours later, I was broken. The Devil had won this particular fight, if not by knockout then certainly on points. In the final analysis, both the Fred and the Devil are worthy contenders for the title of 'the UK's toughest sportive' but it is the Devil that takes the belt. The Fred is brutal, a big puncher that hits hard and fast but it's the Devil, with its extra 120 km, which keeps throwing hill after hill at you, each climb feeling like another jab to the body, each hairpin another right cross hitting its mark, incessantly drawing the power and resolve from within. After the Fred, I felt tired but I was upbeat, whereas after the Devil I was broken and desperately looking to reunite with my 'Adrian' in the comfort of my home. It was as if I had ridden one of those solo 24 hour mountain bike events, of which I have done nine - every sinew of my body was convinced this had been ten. The Dragon Devil, you will take some beating but how you compare with the mainland's finest - the undisputed champion of Sportives - the Alpes Marmotte, I will discover on the 2nd July.

Looking for Winter Training? |

Author

Categories

All

Stage Races

24 Hours 7 hour Enduro Series 12 hour Enduros 6+6 hour Enduros Archives

August 2021

|

| CycoActive - Professional Endurance Cycle Coaching |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed